By Charles Barrett and Desiree Vyas

While it’s true that money isn’t everything, it does allow access to experiences that are important to raising healthy and well-rounded children. When families have more money, they can live in neighborhoods with better-funded schools and provide opportunities for their children to succeed outside of the classroom through music, drama and sports programs. But for children living in poverty, seeing their peers with things they want but their families struggle to afford can be difficult. And though we would expect those from lower socioeconomic groups to feel as if they don’t have enough, the popularity of social media has led young people from middle-class backgrounds to also feel stressed about keeping up with their friends. So what can families do to help their children understand money and the value of a dollar? How can parents and guardians help youngsters know the difference between wants and needs? And last, how can children learn to not compare themselves with others? To avoid the rat race of buying more and doing more in a never-ending cycle of playing catch up, check out the ideas below.

Coping With the Pressure of “Keeping Up”

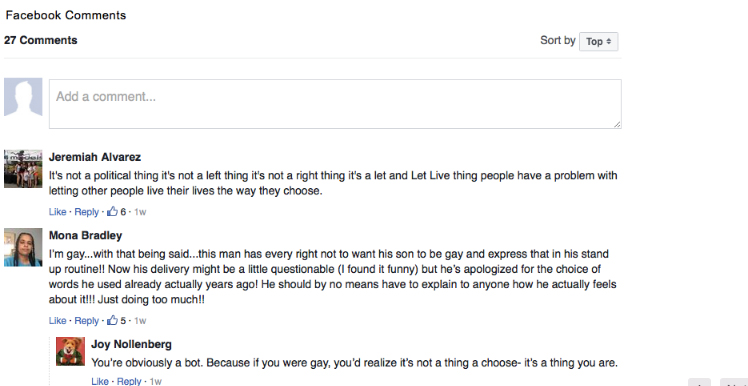

On top of the pressures facing families who are trying to raise children in a world that is becoming increasingly competitive, many have experienced their youngsters asking for things they simply cannot afford. But more than not being able to give their children what they want, families are also overwhelmed by the stress of keeping up with the lifestyles of their children’s peers. As young people are bombarded with their friends’ Instagram or Snapchat stories showing the latest trendy merchandise, even if they never say it, at one time or another, children may think to themselves, ‘Why can’t I have what [insert friend’s name] has? Or, ‘I wish that my family could buy me [insert desired item]. It’s not fair!’

Although it is difficult for any parent or guardian to hear these words from their children or to see them sad because they can’t get what they want, not being able to provide these things is also an opportunity to teach young people invaluable lessons about patience, priorities, discipline and healthy comparison.

Patience. Families can help children understand that although they may not have what they want today, eventually—especially if they work hard—they will be able to afford these things. In other words, not now does not mean never.

Priorities. When youngsters ask for things they want, families can use this as an opportunity to explain the differences between wants (e.g., more toys, the latest fashions or a newer phone) and needs (e.g., adequate food, shelter and clothing).

Discipline. Related to patience and priorities, families can teach children about helpful behaviors that will lead to having more money. Encouraging them to consistently save, even small amounts of money, is one of the most important lessons families can teach and model for their youngsters.

Healthy Comparison. As Theodore Roosevelt once said, “Comparison is the thief of joy.” To help children understand the differences between healthy and unhealthy comparisons, explain to them that unhealthy comparisons lead to feeling sad, inadequate or even ashamed; further, unhealthy comparisons don’t motivate them to become better people. On the other hand, healthy comparisons can be used to inspire young people to achieve the things that really matter in life. Ask your children who inspires them and why, and what they can do to become more like them.

Exposing Children to What Is Possible with Their Own Money

As families teach and model patience, priorities, discipline and healthy comparison, they can also help their children to think differently about money. Rather than simply seeing it as a means to buying what they want, explain that money is a tool that can change a person’s quality of life. Talking to young children about saving can be done in developmentally appropriate ways. For example, families can give their youngsters $1.00 or $5.00 per week either as an allowance or as payment for completing certain household chores. In addition, parents can require children to save a certain amount (e.g., 25 percent) by holding this for them. After a few months, children will learn the value of a dollar by seeing how much they have saved. As an added lesson in responsibility, young people can use their savings to buy what they want (not need). And as you may already know, when children are expected to pay for what they want, they may not want what they thought they wanted with your money.

Inspiring Children to Earn Money

Especially during the teenage years, it becomes more important for families to have serious discussions with their children about earning money. Specifically, the youngsters should be asked, “What is your plan for making money so you can provide for yourself?” or “What career path do you plan to pursue in order to earn a living?”

As school psychologists, we believe every child has a purpose—a reason why they exist—and a gift—something they do very well and almost naturally. Therefore, adults—parents, guardians, educators, mentors, community leaders—must help them figure out their purpose and support them in developing their gifts. When young people know they are good at something and are encouraged to develop their skills in these areas, if opportunities to make money present themselves, they will be prepared to take advantage of those situations. For example, we have worked with elementary school-age children who were exceptional at mowing lawns and gardening. With the right guidance, they could have bright futures as landscapersliving fulfilled lives.

As you follow your children’s interests, help them develop their gifts and a commitment to hard work. As a result, not only will they be inspired to solve problems facing their generation and community, but they will also be motivated to do more than just make money: They will create wealth to impact future generations.

Charles Barrett, Ph.D., NCSP, is lead school psychologist with Loudoun County Public Schools and an adjunct lecturer in the Graduate School of Education at Howard University. Follow him on Twitter @_charlesbarrett and Instagram @charlesabarrett using #itsalwaysaboutthechildren.

Desiree Vyas, Ph.D., NCSP, is a school psychologist and faculty member with Loudoun County (Virginia) Public Schools’ APA-accredited doctoral internship program in Health Service Psychology. Follow her on Twitter @DesireeVyas and Instagram @desiree_vyas.

Original article was published here.

Facebook Comments