BY NICOLE LAPORTE,

Earlier this year, a heartfelt short film about an African American father who has to endure the (arduous and terrifying) task of doing his young daughter’s hair for the first time captured the entertainment industry’s attention by taking home an Oscar. The film, created and directed by Matthew A. Cherry, had originated as a Kickstarter campaign in 2017, where it raised $300,000—its goal was $75,000—and then was brought to the attention of Lion Forge Animation, which came on board as a producer.

When it debuted online, the film, which is voiced by Issa Rae, went viral, and it was added as a short before theater screenings of Angry Birds 2. (Sony Pictures Animation also came on as a producer.)

Then came the Academy Award for Best Animated Short.

Hair Love not only made a name for Cherry, who has since forged a production deal with Warner Bros. Television, but for Lion Forge Animation, a mission-driven animation studio based in St. Louis that is dedicated to bringing diverse voices and stories to both small and large screens.

The company is one of the few Black-owned animation studios in existence and was created as a sibling to Oni Lion Forge Publishing Company—an independent publisher of comic and graphic novels such as Puerto Rico Strong, Stumptown, and Tea Dragon Society—that was originally founded in 2011 to reflect and champion the voices of underrepresented groups such as African Americans, Hispanics, members of the LGBTQ community, and women. The animation studio, which was established a few years ago, carries on that mandate, specifically as it relates to the notoriously white, male-dominated animation industry. Not only is there a severe shortage of Black directors and creators, but animated films themselves, particularly older ones, are rife with stereotypes and plots in which African American characters are relegated to the funny sidekick role, at best. At worst, they’re depicted as racial stereotypes or victims in need of rescue by white savior figures.

Lion Forge Animation seeks to change this narrative. “We’re really challenging the expectations of what we’re currently seeing in the media,” says Lion Forge founder Dave Steward II. (Steward is the son of tech billionaire David Steward and the brother of Manchester By the Sea producer Kimberly Steward.)

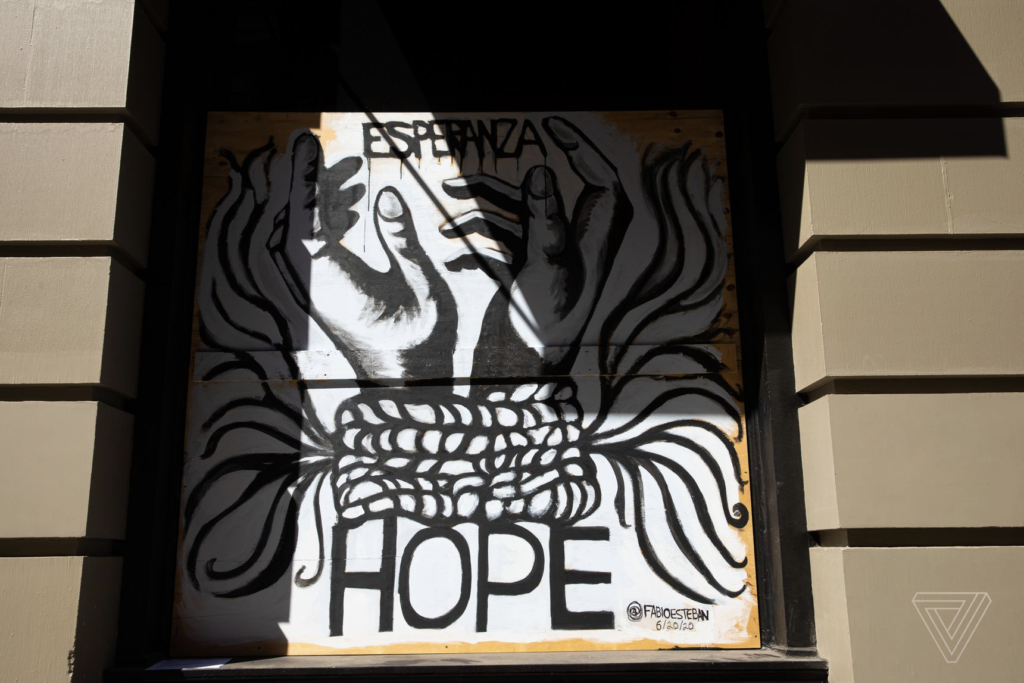

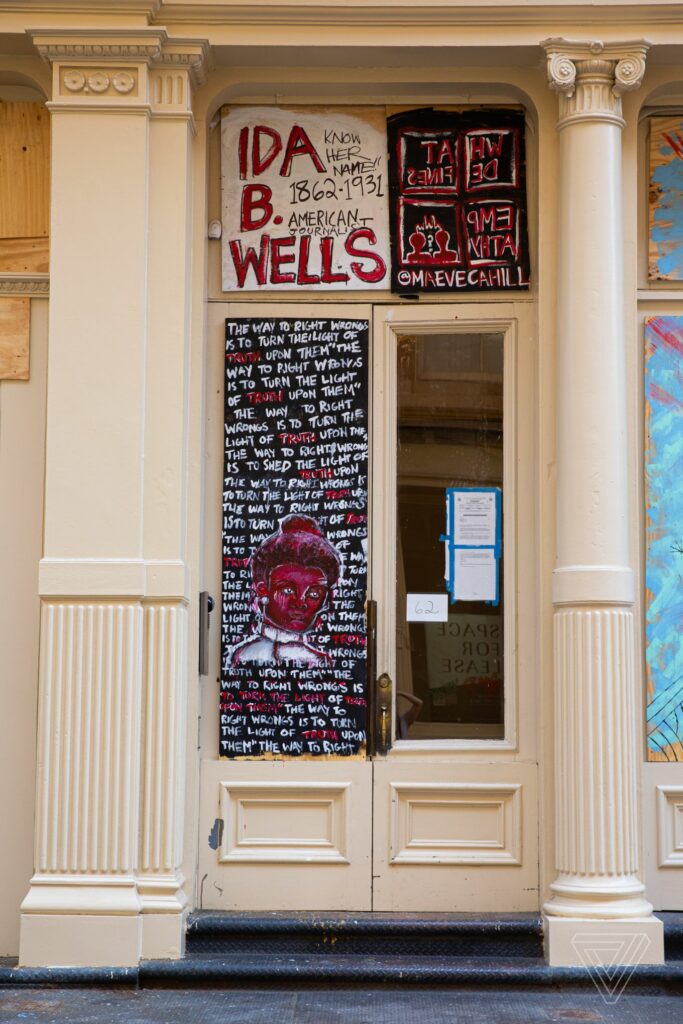

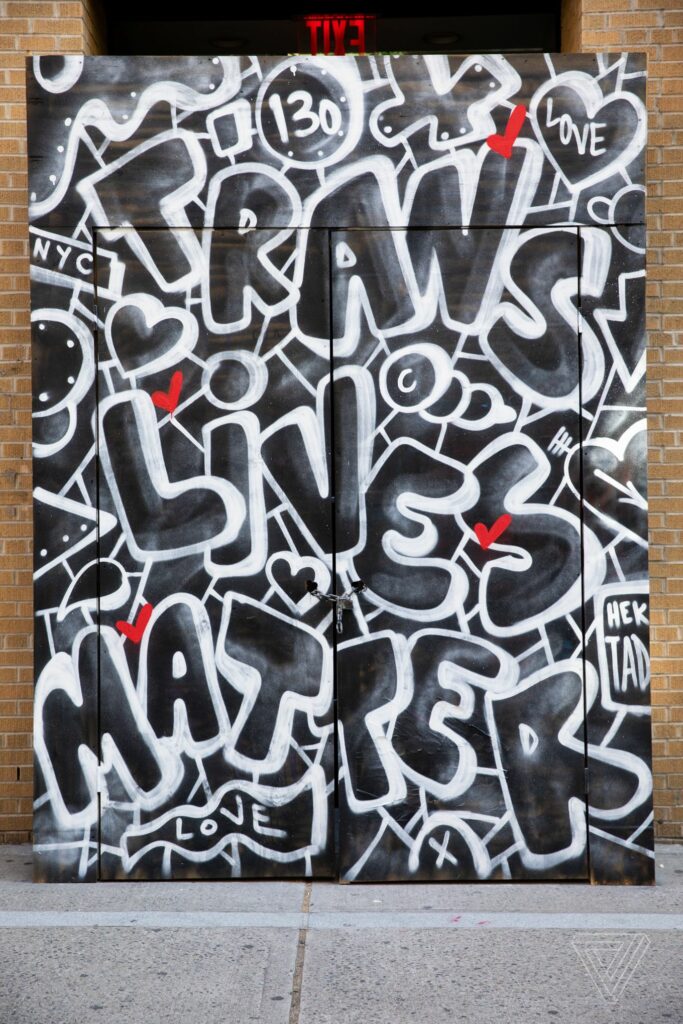

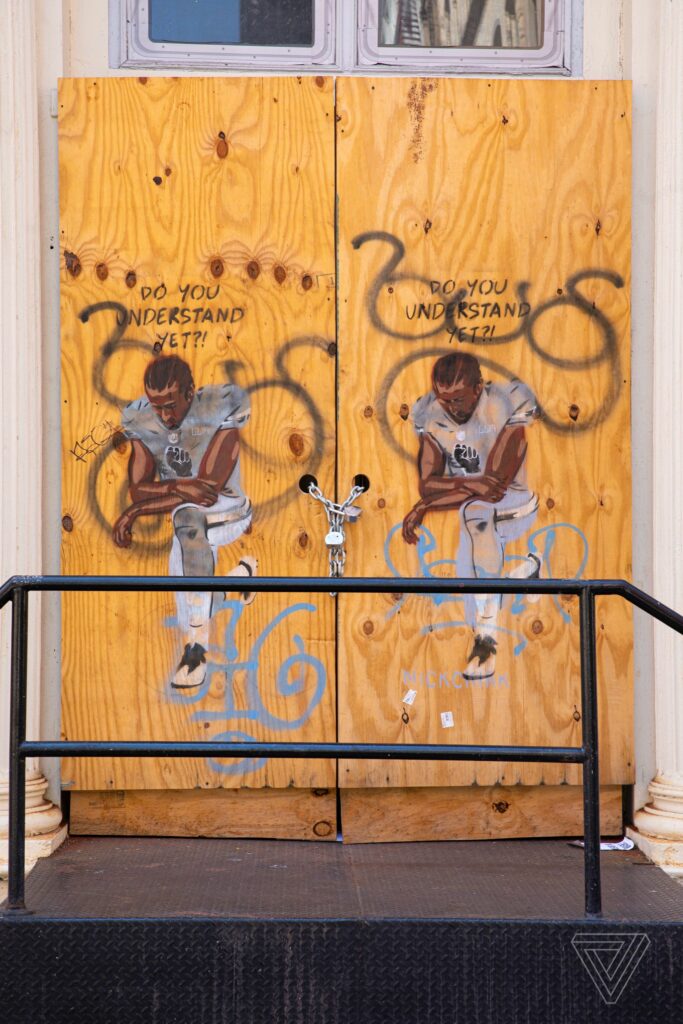

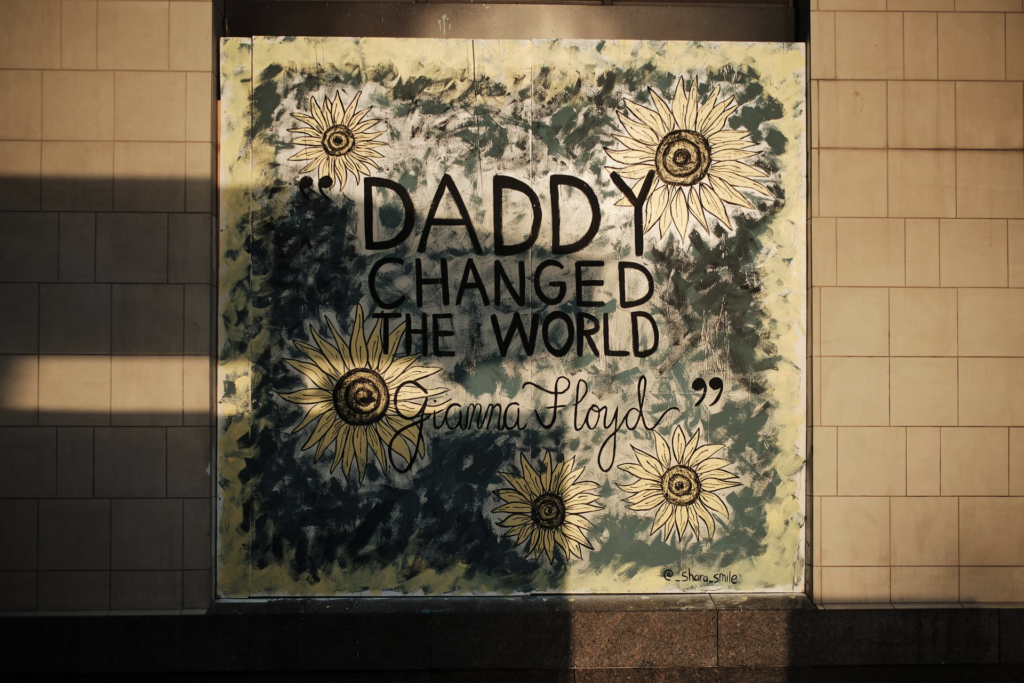

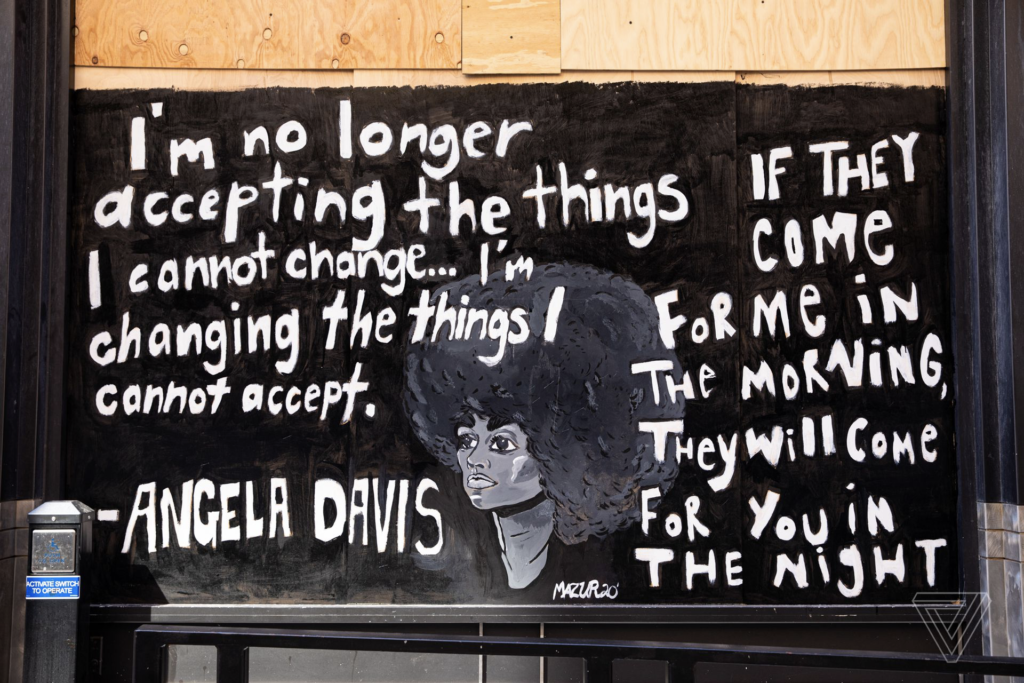

But if Hair Love put Lion Forge Animation on the map, the company is now coming into its own and flexing its muscles at a time when the culture at large is becoming more invested in shining the spotlight on underrepresented voices, thanks to the Black Lives Matter movement and the discussion it’s instigated across the nation. As Hollywood makes strides to self-correct its racial and ethnic lens, Lion Forge offers an opportunity to invest in content that tells stories from the perspective of African Americans and other creators who are not typically given a seat at the table.

Indeed, it represents a far more authentic answer to the problem than some of the awkward (if well-meaning) gestures that the entertainment industry is making in response to BLM—such as changing out white voice actors who have been voicing Black roles on animated shows such as Big Mouth, Family Guy, and The Simpsons.

Lion Forge Animation’s projects, in contrast, not only reflect the stories of underrepresented voices but are created and overseen by individuals from those groups. “We have our own kind of brand of diversity where just being allowed to be in front of the camera, I don’t think that’s enough,” says Carl Reed, president of Lion Forge Animation. “Or just being able to tell stories about Black people and their environment. I don’t think that’s enough. We’ll really feel like we’ve done our job when we can have an animated show with maybe even all white characters, but you don’t know that behind the scenes is Black writing. What does that do to the traditional narrative that says, Hey, there are no new stories. Everything’s been told. It hasn’t been told from every perspective.”

This approach, combined with Lion Forge Animation’s reputation for high quality, has captured the entertainment industry’s attention. HBO Max recently announced that it is turning Hair Love into an animated series—it will be called Young Love—with Cherry serving as showrunner along with TheBoondocks co-executive producer Carl Jones. Lion Forge Animation also has formed a partnership with Ron Howard and Brian Grazer’s Imagine Entertainment to create content for Imagine Kids+Family. Projects so far include Puerto Rico Strong, which will delve into issues such as the effects of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Rico; Chippy Hood, a preschool series about four little chipmunks; and a Black anthology series that will feature Black creators telling stories based on their experiences. It is also working with the Chinese entertainment company Starlight Media to take Chinese IP and turn it into content that melds Chinese and American sensibilities.

As Lion Forge expands in size and scope—it has production studios in Argentina and India and has plans to open another facility in South Korea—it has the potential to do far more than just create memorable short films that expose viewers to worlds not typically examined in mainstream media. Due to its relationship with Lion Forge’s comics arm, the studio is poised to create multimedia franchises, some based on its own comic book IP, on par with what big-league animation studios such as Pixar and Illumination are cooking up. Its partnership with foreign companies such as Starlight Media expands its reach to a global level.

“Our inherent structure kind of lends itself toward franchising,” says Steward II. “Because we have both the publishing side and the animation side. So we’re able to co-develop things that have a far, far reach. We’re always looking at, ‘How do we engage our audience on multiple levels?’”

MAINTAIN CREATIVE AND EXECUTIVE AUTHENTICITY

Even as it begins its path toward global domination, Lion Forge Animation stands by its primary philosophy, which is that minority-focused content must be created, played, and overseen by minorities and not left up to mainstream artists and executives whose perceptions about other groups are ultimately that—perceptions.

“If you kind of break it down, there are three parts to this,” says Steward II. “It’s representation on the screen. It’s representation on the producing side of things. But then also, and I think what’s always missed, is, there needs to be representation in the executive teams that have the power to be able to push the content through.

“Because if you have content that’s, let’s say, is from a Black creator and has a Black cast, but you have non-Black executives overseeing the projects, all too often, I mean, there are stories of those executives using their power to change that content based off of their perception and portrayal of a particular group,” he continues. “So those three things need to happen. As companies really look at this and get serious about it, it’s about changing those three aspects in order to have meaningful content with a meaningful voice that gets put out.”

This formula proved successful for Hair Love. “We had an African American producer, we had an African American director, and we were all kind of pulling for a singular vision,” says Steward II. “We were in our own kind of creative bubble that we were able to work in, free of any kind of outside interference.”

Even Sony Pictures Animation “did not seek to have any kind of approval of what we ended up making,” he adds.

This pure creative space may be hindered somewhat with Young Love, which is “entering into the machine” of HBO Max. But Steward says he’s hopeful given Cherry’s track record and the acclaim garnered by the original short. “Coming into this process from, I guess, success, is helpful. When you have a new project that’s unproven, you’re going to walk into these situations and inherently have” less power. “Given the fact that we have the track record of success in doing this definitely gives us a better opportunity and vision. At the end of the day, that’s what Sony and HBO bought into for the series. Making sure that we capture that same magic that we had in the short.”

A MULTIMEDIA APPROACH

Lion Forge’s multipronged media structure means that it can do much more than just release a movie or TV show. A few years ago when it had the license to Voltron, the 1980s animated series, it partnered with DreamWorks Animation, which rebooted the show for Netflix in 2016. To complement the show and feed fandom, Lion Forge created a Voltron comic book spinoff that was published alongside the Netflix series.

“We were able to create a derivative series that worked with the main stories [DWA] was telling and were able to extend the content over the year, versus having the content released twice,” says Steward II. “So you had a constant feeding to the marketplace of content. That worked very well for us and is kind of the basis of our plans for how we’re releasing content from an animation standpoint going forward.

“If you’re releasing something, it only exists for that certain period of time. Whether you have a yearly or a multiyear series that’s being released on SVOD or a movie coming out and it’s going to be a couple more years ’til the next movie, how do you bridge those moments that you’re releasing content and keep your audience engaged? Comics offer that unique opportunity to keep in contact with fans.”

In the case of Voltron, some fans were outraged when the Netflix series maintained loyalty to the original series by burying the storylines of gay characters in the final season. Lion Forge Animation had no creative input on the series, but the incident points to how the company and its brand are best served when Lion Forge is in the driver’s seat, and the importance of having that creative bubble.

Nonetheless, the Voltron model points to how the company can mine both its own IP and create new titles that it can then blow out across two platforms in order to build and support fan bases.

A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

Don’t be fooled by Lion Forge’s St. Louis address. Although that’s the company’s hub, where preproduction and development all take place, the company’s growing global footprint of production studios means there is not only more manpower but more influence from other pockets of the world.

“We’re all about perspectives and challenging those expectations,” says Reed. “So there are creators in Korea and Malaysia who don’t necessarily get the spotlight either. What stories are we missing out on there? We’re excited to play in all these waters and be able to hopefully get access to some of the best stories globally.”

Meanwhile, when a particular piece of content speaks to a particular geographic location, the company can leverage its breadth. “Our teams are strong across the board, and content that might be appropriate for Asia or Latin America—we have those teams in-house. So we’re able to really lean on them when we have a story to tell from those perspectives,” Reed goes on.

Steward says that the company has not been hindered by COVID-19, other than a week or so when artists and executives had to take their laptops home and set up a new workspace. Beyond that, production marches on, all the more so as “content distributors and platforms are more voracious than ever needing content and are looking more to animation for opportunities,” he says. He points out how the series The Blacklist, whose production schedule was interrupted by the pandemic, turned to animation to create the final episode.

Reed echoes this, saying it’s business as usual these days. “Hopefully we all social distance by nature. We get behind a computer and start working.”

Original article was published here.