By Alex Horton,

More times than she can count, Mary Tobin walked the verdant grounds of the U.S. Military Academy past Lee Barracks dormitory, named in honor of Robert E. Lee, the Confederate general who killed thousands of U.S. soldiers. But the traitor symbology didn’t end there, or at the paintings and names etched on plazas.

Tobin, who is black, was assigned to inspect the living quarters of fellow cadets during her junior year, a responsibility given to rising leaders. In one dorm room, a white male classmate hung a Confederate flag on a wall to get a reaction. She yanked it down and handed it back without showing emotion, she recounted.

“I never addressed that it made me feel horrible,” said Tobin, a 2003 graduate.

The police killing of George Floyd has triggered a wave of reckoning over racism and identity coast to coast, including at the U.S. Military Academy, among the most isolated and traditions-bound institutions in the country.

Black alumni have described racist encounters with their classmates loud and subtle, from the chow hall to the parade field. But a letter to administrators from recent top graduates underscores the entrenched racism that minority cadets endured to become part of the Long Gray Line.

Several cadets in the Class of 2020 said they were called the n-word, according to a letter signed by nine recent graduates, some of whom are black and all held leadership positions. “I was told that I was going to rob someone because I was Black,” one unnamed cadet said.

Others reported similar language and veiled threats, such as nooses hidden in desks as bleak practical jokes, followed by inaction by faculty.

By not rooting out racism that “saturates its history,” the officers said, “West Point ultimately fails to produce leaders of character equipped to lead diverse organizations.”

In interviews, five black graduates whose time at the U.S. Military Academy spanned decades said their experiences ranged from pride in entering an elite university to the sadness of feeling they could not be their full self in a mostly white school.

The alumni recounted moments of suppressing black cultural and social references among white classmates, fielding questions about black hair and hearing whispers that athletics — not their academic rigor — led to their offer to attend.

“I love West Point,” said Tobin, a former Army signal officer. “But it is a beautifully painful experience.”

The academy takes the long view in minority admissions. In 1968, when the equal opportunity admissions office opened, only 68 African Americans had graduated since the U.S. Military Academy’s founding in 1802, said Maj. Kendrick Vaughn, who recently left his position as the diversity admissions officer.

There were 72 black graduates in Vaughn’s own Class of 2008, he said. This year’s incoming class saw 214 admitted African Americans out of 1,240 total cadets.

In a statement, the academy said it launched an inspector general review “of all matters involving race,” spokesman Lt. Col. Christopher Ophardt said. That review was partly prompted by the letter, along with other initiatives at higher levels, Ophardt said.

“We take seriously all forms of racial inequality that marginalize or devalue members of our team,” he said.

Tobin, an adviser for the officers who penned the letter and a mentor to some, said the group was emboldened after Defense Secretary Mark T. Esper called on leaders last month to weed out racism. “A diverse and inclusive DoD draws out and builds upon the best in each of us,” Esper said in a video message. “It brings out the best in America.”

But the rising number of black cadets hasn’t spurred enough change, alumni said. The letter was a time machine back to the halls where white cadets made subtle comments and jokes “that you have to smile and suffer through,” said Michael Armstrong, a former infantry officer in the Class of 1987.

“The more things change,” he said, “the more they stay the same.”

Jamal Robinson, a 2010 graduate and former chemical officer, said a stark reality for black cadets was the realization that a commission would never be enough for some classmates.

“As much as I love my country, and the U.S. Army, it hurts someone can treat you in a racist manner on the same team,” he said. “You know racism exists in your country, but it’s the same country you’re willing to lose your life for.”

The experience is doubly trying for black women navigating the mostly white, mostly male culture of the Army officer corps, alumni said. There was a record high of 38 black women graduates in a class of 1,107 this year, officials said.

Shalela Dowdy, a former air defense artillery officer, Class of 2012, said there were times she was either the only woman or only black cadet in a class, where her classmates urged her to be less outspoken about her blackness. In a search for mentors, she flipped through previous yearbooks and wrote down the name of the few black women listed and got in touch, she said.

Those earlier black female graduates had been in even smaller numbers, said Paula Browning White, a former quartermaster officer who recalled around a dozen black women in the Class of 1987. Passionate about church choir, White was advised by her mother to avoid hanging out and singing with only black cadets, she said.

The protestant choir was all white, she said, and she gravitated to the gospel choir as a humming refuge.

“You could let your hair down and be yourself,” she said.

The graduates also recommended to divest from all Confederate traces that dot the grounds, such as Lee Barracks, a plaza bearing the name of Confederate officers and several paintings — including one of Lee on a white horse led by a slave, which resides in a library.

Further reminders of the Confederacy await the Class of 2020. About a third of them have left for training at some of the 10 Army installations named after Confederate commanders, academy officials said.

“We’re honoring people who were traitors to our country and keep my ancestors as slaves,” Dowdy said of the names. “It keeps their memory alive.”

Original article was published here.

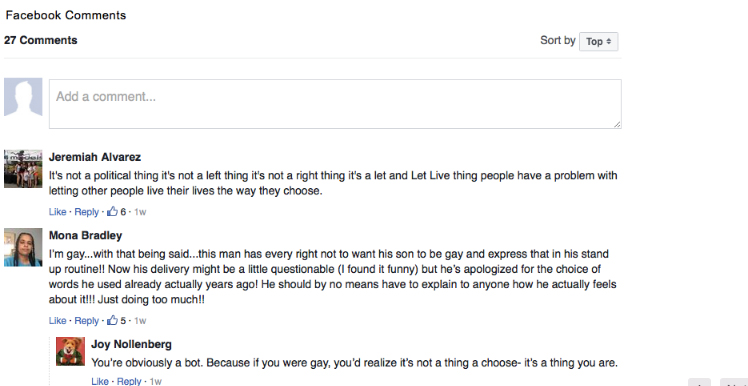

Facebook Comments