By Will Hobson and Ben Strauss,

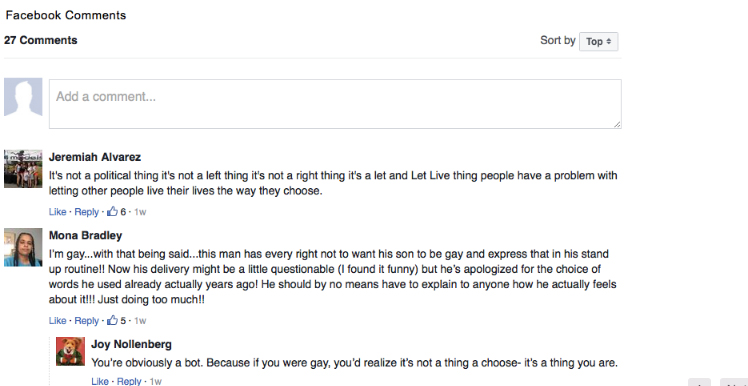

California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) confirmed the latest attack on NCAA amateurism rules, signing a bill Monday that permits college athletes in the state to get paid for their name, image and likeness through endorsement deals, sponsorships, autograph signings and other similar income opportunities.

Initially proposed by state Sen. Nancy Skinner, a Democrat from Berkeley, the Fair Pay to Play Act drew social media support from NBA stars LeBron James, Kevin Durant and Draymond Green as well as U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.). The law carries the potential to force major colleges and universities to allow scholarship athletes to make money through income avenues that the NCAA has warned for decades would bring about an end to college sports as we know it.

But with the long wait until it goes into effect — Jan. 1, 2023 — it will be some time before its actual impact will be clear.

What does the law change?

The law allows college athletes to sign the same types of endorsement deals and sponsorship agreements as professional athletes, and it prohibits schools and the NCAA from punishing athletes who take such income. It essentially would create an Olympic-style income model in California: Schools will not be forced to share the revenue they generate from sports but must permit athletes to cash in on their name or status, if they can.

There are some limits on potential athlete income. Before the bill was passed by the California Assembly, a provision was added to the legislation to prevent athletes from signing deals that conflict with a school contract. An athlete at a Nike-sponsored school couldn’t sign an endorsement deal with Adidas, for example.

Once considered unthinkable by college sports power brokers, allowing name, image and likeness income for college athletes has emerged in recent years as potential middle ground in the long-running debate over NCAA amateurism rules.

As the recent Justice Department investigation of Adidas’s youth basketball operations showed, major shoe companies already are trying to pay top high school recruits. According to CBS Sports, a recent anonymous survey of more than 100 Division I men’s basketball coaches found 77 percent support allowing their athletes to make name, image and likeness income.

Has the NCAA responded?

With strong opposition, as expected. Earlier this month, the NCAA Board of Governors sent a letter to Newsom that read: “If the bill becomes law and California’s 58 NCAA schools are compelled to allow an unrestricted name, image and likeness scheme, it would erase the critical distinction between college and professional athletics and, because it gives those schools an unfair recruiting advantage, would result in them eventually being unable to compete in NCAA competitions.”

The Board of Governors argued, “A national model of collegiate sport requires mutually agreed upon rules” and that the NCAA must set the policies governing college sports instead of “one state taking unilateral action.”

The letter followed comments by NCAA President Mark Emmert, who in July sent a letter to California lawmakers warning that the bill, if passed, could result in the organization pulling national championship events from the state, among other potential adverse impacts.

“The bill threatens to alter materially the principles of intercollegiate athletics and create local differences that would make it impossible to host fair national championships,” Emmert wrote. “As a result, it likely would have a negative impact on the exact student-athletes it intends to assist.”

Emmert and others have pointed to the unanswered questions about potential ripple effects of allowing athletes to sign sponsorship deals. What’s to stop Nike co-founder and Oregon booster Phil Knight from using his company’s resources to sign top recruits for his alma mater? Or to prevent bidding wars between boosters for Alabama and Clemson seeking to curry favor with football recruits by paying exorbitant amounts for their autographs?

After Newsom signed the bill Monday, the NCAA responded with a statement that read, in part: “As a membership organization, the NCAA agrees changes are needed to continue to support student-athletes, but improvement needs to happen on a national level through the NCAA’s rules-making process. Unfortunately, this new law already is creating confusion for current and future student-athletes, coaches, administrators and campuses, and not just in California. . . .

“As more states consider their own specific legislation related to this topic, it is clear that a patchwork of different laws from different states will make unattainable the goal of providing a fair and level playing field for 1,100 campuses and nearly half a million student-athletes nationwide.”

How have California colleges and universities responded?

In line with the NCAA and the Pac-12 Conference, also in staunch opposition. In a letter to lawmakers, a University of California official raised concerns that the bill would sap sponsorship money that currently goes to universities, leading to budget cuts and the potential elimination of sports that don’t generate the millions in revenue seen by football, men’s basketball and, to a lesser extent, baseball and women’s basketball.

Could this legal threat actually undo amateurism?

It remains to be seen, but there are reasons to be pessimistic this bill will be implemented in 2023 as written. A clause allows the bill to be amended if the NCAA changes its policies. An NCAA committee — created this year after this bill was proposed — is examining the organization’s rules regarding name, image and likeness income.

However, the bill’s passage represents a new challenge, and continued pressure, on college sports’ economic structure, which has remained mostly intact following several high-profile legal challenges. Andy Schwarz, an economist who consulted with Skinner’s staff on writing the bill, found significance in the unanimous support the legislation received: 72-0 approval in the State Assembly.

“I think people wanted to get on the right side of history,” he said. “The fact that no one wanted to go on the record against this is a big deal.”

Original article was published here.