By Eric Spitznagel

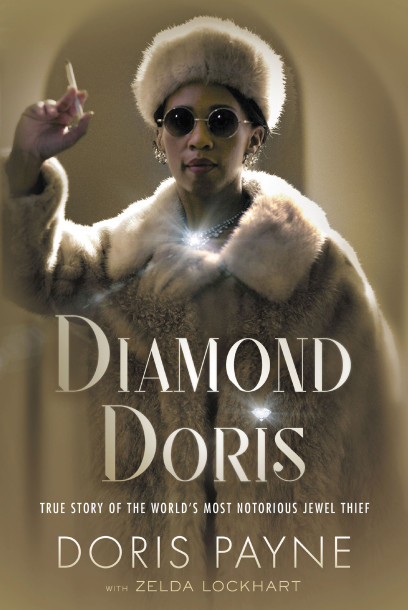

By 1975, Doris Payne had been stealing precious diamonds around the globe for several decades. But when the 44-year-old set her sights on her latest target, the world-famous Bulgari jeweler in Rome, she thought she’d met her match.

The handsome young clerk didn’t have that special quality she looked for in a mark, the “combination of eager to please and stupid,” she writes in her new tell-all memoir, “Diamond Doris” (HarperCollins), out Tuesday.

He moved too fast, was as watchful as a hawk and didn’t give her a chance to confuse him.

“This dude was trained like a stripper,” Payne writes. “But I was gonna find a way to flip it on him.”

She moved at a dizzying pace, putting on and taking off rings and necklaces until the clerk wasn’t able to keep up. As she slipped a yellow diamond ring worth thousands onto her middle finger, “he didn’t notice my hand move like a snake,” Payne writes.

She asked to use the powder room, then disappeared into the streets of Rome before the clerk realized what had happened.

It was the last in a five-day, four-city larceny tour in which she also walked off with a $55,000 watch at Van Cleef & Arpels and several diamond and emerald pieces from Garrard & Co., the London jeweler to the British crown.

By the time she was on a plane back to the United States, “I was carrying what would amount today to nearly $1 million worth of [jewelry] on me,” she writes.

It was just business as usual for the West Virginia native, whose career started when she was 16, and she and a girlfriend would take three-hour bus trips to Cleveland to practice stealing watches from Woolworth.

Twenty years later, she was an international jewel thief who traveled the world under 32 aliases with at least nine passports.

Now 88 and ready to confess to everything, she tells how a nurse was transformed into the world’s most famous jewel thief. Though commuters every morning might have seen her as “some black woman who rode in the back of the bus like every other black Cleveland woman headed to her subservient job,” Payne writes, “on weekends, I was Doris Payne, jewel thief in training.”

Born and raised in Slab Fork, a mining town in West Virginia, Payne was the youngest of five children and the most protective of her Cherokee mother, who was physically abused by her African-American father, a struggling coal miner.

Her parents’ unhappy marriage was at least partly responsible for Payne’s life of crime. Marriage, she writes, “just ties you to brutality.” She was determined never to be financially dependent on a man.

“I would always make my own money,” she writes. “And I was going to have to take care of me and mine.”

She was also driven by resentment over racial inequality. She would read her mother’s Harper’s Bazaar magazines, seething that the white models in diamond bracelets “weren’t better than me.”

When she found a job in Cleveland, working as a hospital nurse, she would take trips to Pittsburgh to swipe jewels.

Her first big score happened in 1952, when she was just 23. Payne walked out of a Pittsburgh jewelry store with a diamond ring valued at $20,000.

But she was so paranoid that she’d been followed, she ended up spending the night in the bathroom stall of a Greyhound station. “I fell asleep with the [stolen] ring pinching my left breast,” she writes.

The next day, she walked back to the jewelry store, guilty and determined to return the stolen diamond. But she ended up wandering into a resale store just blocks away, selling the ring for a $7,000 profit (about $65,000 today).

Payne learned that if she convinced jewelers to bring out more than five pieces to show her at one time, “they were shy about reporting that to the police, who would send a report of the store’s negligence to their insurance company,” she writes. “I had to practice making it their fault.”

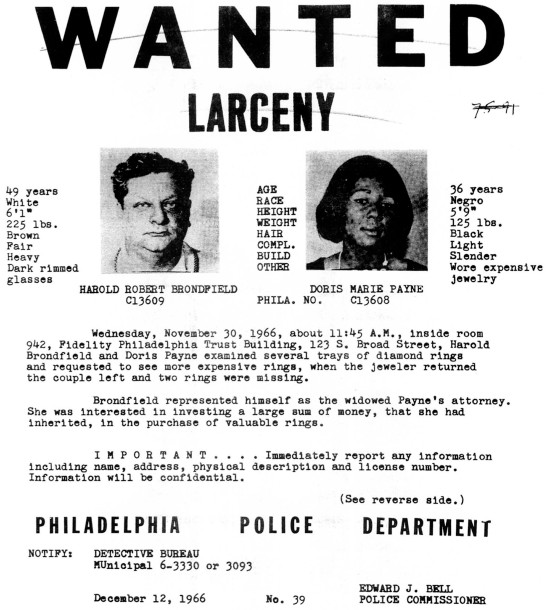

In 1957, she began dating an Israeli with deep ties to the criminal underground. Nicknamed “Babe,” real name Harold Bronfield, he was a 6-foot-4 Cleveland man with enough legal muscle to protect Payne when necessary.

When she was identified as the culprit in a jewelry heist in Philadelphia, Babe’s well-connected lawyers “handled” it, negotiating with the judge for a guilty plea without time served.

But photos of Payne eventually hit the papers, forcing her to travel to smaller cities and towns where she wouldn’t be recognized. Stealing became even more difficult when her protector Babe died in 1968 from complications from cosmetic surgery.

By the early 1970s, she decided it was too dangerous for her in the US and she moved her operations to Europe, “where diamonds make their first stop on the black market.”

Her first destination, during the summer of 1974, was Monte Carlo. She targeted Cartier and made off with a 10-¹/₂ carat diamond ring worth half a million.

She didn’t make it far. Her biggest mistake, she says, was forgetting to “change my clothes before heading to the airport.” The police got to her before she boarded the plane.

Amazingly, despite several full-body searches, they never found the ring. She hid it first in some Kleenex, pretending to have a nose cold. And then she borrowed a needle and thread from a guard to fix the hem of her skirt and used it to whip-stitch the stolen ring into the hem of her pantyhose, where it stayed for months.

“It was a stalemate,” she writes. “They couldn’t find the piece and couldn’t hold me forever for a crime they couldn’t prove.”

Just after her 50th birthday in 1980, Payne pulled off her most impressive escape yet. This time she flew to Zurich and consumed too many cocktails with her driver, breaking her No. 1 rule: No alcohol.

As she drifted in and out of consciousness, she had only fuzzy memories of wandering into a store selling Rolexes, she writes. She ended up at a club, where she danced till late and was surrounded by police at the coat check when she tried to leave.

They put her on a train bound for the embassy in French Switzerland, and at some point during the early morning, Payne claims, she asked permission to use the bathroom and jumped off during a stop.

She then wandered through a dark cornfield until she found a taxi willing to take her to a hotel in Zurich.

Only then did she realize she had a stolen Rolex on her, although she had no memory of taking it. “I didn’t know what the hell was wrong with me,” she writes. “Maybe I’m too old for this s–t, I told myself.”

Payne eventually did do time, but only a handful of years, and never for the crimes that made her infamous.

She was sentenced to 12 years in 1999 for stealing a $57,000 ring in Denver but only served five. She was arrested again in 2011, when the then-81-year-old was in the middle of a California crime spree, stealing diamonds from Palm Desert to San Diego. Today, she lives alone in a penthouse rental in Atlanta — she lost her Shaker Heights home to a foreclosure, and her savings have long since been depleted — and enjoys occasional visits from her adult children.

Though she claims to be retired, she was last arrested just two years ago, in the summer of 2017, for allegedly leaving an Atlanta Walmart with $86 worth of groceries and electronics.

According to Payne’s co-author Zelda Lockhart, the world’s most famous jewel thief isn’t different from any other successful person trying to redefine themselves later in life.

“They continue to get up at the same time and look to be useful in the same ways that they made their living before,” Lockhart told The Post. “Doris is no exception. She enjoyed her job, and when the industry became more sophisticated with surveillance cameras and international records available through the Internet, it was time to retire . . . but, oh well.”

Original article was published here.