Late last year, tragedy struck Nashville, Tennessee: Prince’s Hot Chicken Shack was forced to close “indefinitely” after a car crashed into the building at a strip mall where the restaurant is located.

Prince’s is the original purveyor of Nashville hot chicken — though you might not know it. A recent profile in The New Yorker focused on Prince’s and its current owner, André Prince Jeffries. As the story goes, Jeffries’ great-uncle Thornton Prince III had some caddish tendencies that one day spurred his girlfriend to seek retribution by saturating his fried chicken in cayenne pepper and other fiery seasonings. “Prince was expected to suffer, and did,” The New Yorker recounts — but he also loved the dish and eventually opened a restaurant dedicated to its sale, establishing hot chicken as a soul food staple.

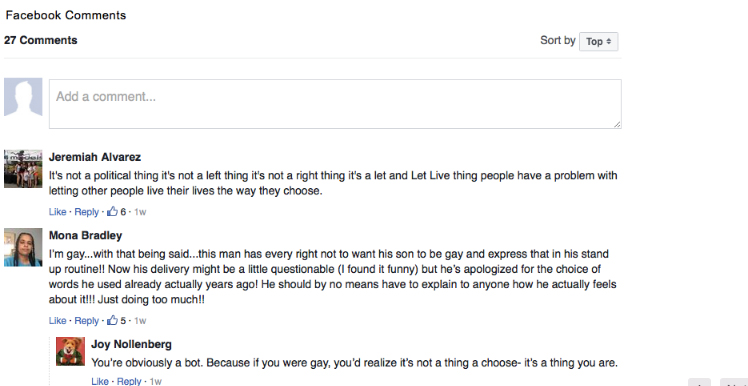

Now, though, “Nashville hot chicken has jumped the shark,” Adrian Miller, a James Beard Award-winning author and food scholar, told HuffPost. The flavor has been co-opted and reborn in various permutations: Miller said he’s seen “Nashville hot oysters” in Denver, while Ohio-based grocery chain Kroger sells “Nashville-style hot chicken” potato chips.

Even in Nashville, the dish’s history has been muddled: As Eater noted in 2017, the website Food Republic declared that John Lasater, the white head chef of Hattie B’s Hot Chicken, had “launched the Nashville hot chicken craze.” Food Republic also published an article in 2015 that listed 27 restaurants outside of Nashville to go to for hot chicken.

But at most of these places, “when the server comes and you ask them the story behind Nashville hot chicken, in many cases, they have no idea,” Miller sighed. Despite the fact that this is just one specific dish and its origins are well-established in Prince family lore, hot chicken’s black roots are being lost.

It’s just one of the ways soul food’s history has been muddled.“

“Soul food, as we understand it, is a hybrid cuisine,” Miller explained. Several culinary traditions come together under its umbrella: foods indigenous to West Africa that arrived in America with the slave trade, like leafy greens and rice, as well as dishes the European elite were feasting on 400-500 years ago, like macaroni and cheese, sweet potato pie and chitterlings (aka “chitlins”).

“All of this food was called ‘Southern’ cooking” for the first half of the 20th century, Miller explained, and black cooks were “seen as its guardians.” But in the 1960s, there was a significant shift: As the idea of a black consciousness emerged, food united black Americans around a cohesive identity — one that also involved music, language, dress and literature.

As a result, black activists “said that ‘soul food’ was stuff that white people couldn’t understand. They said that white people couldn’t understand things like ham hocks, greens, a whole bunch of various soul food dishes,” Miller said. “But that was news to white Southerners because they’d been eating the same thing for several centuries.”

This new effort to elevate black culture and power inadvertently opened the door for the inherent blackness of this food to be erased later on. This “artificial separation,” in Miller’s words, of “soul food” and “Southern food” meant that the shared history of the two cuisines was lost, even though their offerings overlapped. The consequences became apparent decades later, when, after Sept. 11, 2001, Americans’ desire for comfort food exploded, Miller explained.

“Some suggest that 9/11 was such a shock to our national conscious that it spurred this desire to find out what it means to be American,” he said, “and these regional expressions of cultural identity were explored more. And Southern food — it’s just delicious, right? So people dove in.”

At the same time, food television was beginning its popular ascent. The national interest in comfort food made the cuisine a natural subject for TV — “and unfortunately, a lot of the people that make decisions in media went to white cooks,” Miller said. “So white cooks were the ones getting a lot of the publicity and financial opportunities out of cooking this food.”

For example, Paula Deen’s first solo show on the Food Network, “Paula’s Home Cooking,” premiered in November 2002. The first episode featured her promising to deep-fry a turkey and whip up “the gooiest, chewiest pumpkin gooey butter cake that this good ol’ Southern girl knows how to make.” Meanwhile, Art Smith became famous for his fried chicken, cooking for the likes of President Barack Obama, Oprah Winfrey, and Lady Gaga.

Many viewers were learning about these dishes for the first time on TV, where they saw largely white people making “Southern” food. If those white chefs didn’t acknowledge the history of this food, then their audience wouldn’t know about it, either.

The same goes for the restaurant landscape. “When you think about high-end restaurants having things like fried chicken or grits or biscuits on the menu, these are foods that are deceptively difficult to make,” Dr. Marcia Chatelain, a Georgetown University professor of history and African-American studies, told HuffPost. “African-American cuisine is sometimes disregarded because it comes from the context of people who were enslaved or people who were poor and doing the best with what they had. The technique and the precision necessary to make these foods good is sometimes obscured.”

One of the most egregious examples came in 2016, when high-end department store Neiman Marcus came out with a new holiday offering. For the bargain price of $66 — plus $15.50 for shipping! — customers could purchase four trays of pre-cooked and frozen collard greens that had been “seasoned with just the right amount of spices and bacon.”

It’s not clear where Neiman Marcus’ recipe came from, nor which chef (or chefs) may have prepared the greens for the store. But the listing went viral nonetheless, as flabbergasted black internet-goers shared the page with the hashtag #gentrifiedgreens. Many also pointed out that collard greens are traditionally cooked with ham hocks or smoked turkey, not bacon. The Root, a black-centric digital magazine, actually bought the greens and did a taste test. The Root’s assessment: “The greens were straight garbage.”

Beyond the questions of authenticity, Neiman’s greens spoke to another major consequence of soul food’s commodification: price increases. The department store advertised collard greens to customers who were willing to pay more than $80 to get the dish to their door — and the product sold out. But go to an authentic soul food restaurant, like Peggy’s in Memphis, Tennessee, and you’ll find a side order of greens runs about $3.50. Even in a more expensive city like New York, a side of greens costs one-tenth of what it did at Neiman Marcus; Harlem mainstay Sylvia’s offers its collards for $6.50.

“A lot of it is just context. Once you have a white tablecloth restaurant and nice decor, and you’re in an ‘amenable’ part of town, you can add a premium to anything, and people will pay it,” Miller said. “You could not get away with that kind of pricing in a soul food restaurant,” he added, because “soul food is associated with poverty. So it’s like, why are you charging this much for this food?” Moreover, patrons at an authentic soul food joint “are probably going to be working-class, not the hipster crowd.”

What that means, though, is that these foods have become less accessible in the spaces and neighborhoods established by the communities that invented them. “It’s one thing to highlight the food, but when you separate it from the material, economic, social, political and racial realities that created it,” things get dicey, Chatelain said.

Influential chefs like Deen and Smith, who “built their culinary reputation on the food of communities that don’t have access to the acclaim or the revenues or the means of financial security and opportunity” that comes from having a larger platform, have “a responsibility … to make sure they have a clear understanding of the origins of what they’re preparing,” she added.

As Eboni Harris wrote in High Snobiety in 2017, this erasure of black influence “isn’t a new phenomenon.” Harris specifically called out jazz and rock music as having been stripped of their black roots, while the appropriation of black language and style have also been subjects of debate.

When it comes to food, at least, Miller is of an inclusive mind. Anybody should be able to cook whatever food they want, he said, “as long as they respect the tradition, they meet the flavor profiles, and they give a nod to the source.” And as a law school graduate, he’s a realist: “Maybe it’s the lawyer in me, but the logical conclusion of not believing that [people can cook outside their tradition] is that black people can only make African heritage food. … And I don’t think that’s right.”

The history of food is so interconnected, too, that it would be near impossible to draw strict lines of which people can cook which foods. Take chicken and waffles, for example. Chatelain says the dish was created after the Great Migration brought black people to the North in droves, and it’s a great example of a soul food staple that has been divorced from its roots. “People [went] out all night to clubs and [wanted] to have breakfast and dinner at the same time,” she said. “I don’t know if that would necessarily be considered Southern food, but it’s considered soul food.”

Miller disagrees. “I argue that chicken and waffles actually came from Europe,” he said, explaining that German immigrants brought the combination of creamed chicken and waffles to the U.S. When the dish reached the South, he said, the chicken was just fried instead of creamed. To Miller, when white chefs cook chicken and waffles, the dish isn’t being appropriated, it’s “just going back home.”

At the end of the day, it’s about acknowledging that food is much more than sustenance. “We have to take history seriously,” Chatelain said. “Every restaurant is not just feeding people. They’re also telling a story, and they’re trying to elicit emotions about connection, about family, about community — about the past or the present.”

Original article was published here.