By TRACY BROWN,

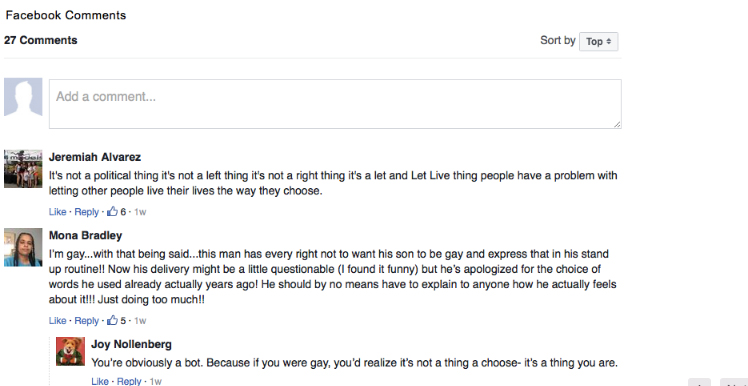

In late June, as a number of animated TV shows announced that white actors would no longer be voicing nonwhite characters, Black N’ Animated, an organization that supports Black students and professionals in animation, released an open letterlaying out specific steps for the industry to take to show its support for the Black animation community.

“There is work to be done,” it read, before a bullet-point list of recommendations: that studios conduct independent audits and investigations into the experiences of their Black employees and any incidents of racism; commitments to hire more Black staff; and training and mentorship programs to support Black employees’ advancement.

The letter came amid nationwide protests over the killing of George Floyd and ongoing discussions denouncing systemic racism in all arenas of culture and society. Various corporations and institutions, including Hollywood studios, had shared statements supporting Black Americans, only to be called on to address the racism and toxic cultures permeating their industries.

Like their live-action counterparts, animation studios have been compelled to assess and reflect on their track record on diversity and inclusion. It’s no secret that animation in the U.S. has long been dominated by white men.

“I’m very happy people are paying attention more. I’m happy studios are trying to do better,” said Breana Williams, a production coordinator and cofounder of Black N’ Animated. “But for me, it’s disappointing that it took Black trauma for the industry to start caring more about trying to uplift Black creatives.”

Anecdotes from members of the Black animation community about being the only Black person — or even the sole person of color — on the staff of animated film or TV productions are not uncommon.

“As much as as we’ve been screaming, kicking at the door [and] trying to get our voices heard in this industry, what I’ve come to find is that there never was enough of us to really make that difference,” said Bruce W. Smith, an animator and creator of “The Proud Family.”

“When I was on ‘The Princess and the Frog,’ for example, I was the only African American animator on the film outside of Marlon West, who was head of effects [animation], but that’s a different department in terms of character animation — the performances that are on film,” Smith said.

This lack of visibility for Black people working in the animation industry is what led Williams and storyboard artist Waymond Singleton to launch their “Black N’ Animated” podcast in 2018.

“We wanted to highlight Black creatives in animation because we didn’t see these individuals being highlighted previously,” Singleton said.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

“Our goal is to inspire, educate and empower Black creatives seeking animation careers,” Williams said. “Waymond and I interview Black professionals in different facets of the animation pipeline, whether they’re writers, production, creative or executive management, so that people can know these jobs exist, and they’re here. There are multiple ways in[to the industry].”

As Black N’ Animated event coordinator Nilah Magruder noted, issues like the need for diversity and the barriers created by systemic racism — within the animation industry and American culture at large — are not new.

“For years Black people have been telling you that these problems exist, and you’ve just never listened before,” Magruder said. “It’s kind of interesting now, because it’s not like we haven’t had protests like this. It’s not like Black Lives Matter wasn’t a hashtag before this moment, but all of a sudden, there’s engagement that we’ve never experienced before.”

The presence and visibility of Black professionals within the industry are key elements for increasing onscreen representation so that TV shows and films feature characters that reflect the diversity of the real world.

“Animation is such a beautiful opportunity for us to explore humanity and how we relate to one another and what connects all of us,” said Taylor K. Shaw, the founder and chief executive of Black Women Animate. “Animation is a key piece of the puzzle when it comes to how Black people are seen and represented because it’s storytelling, and it is storytelling that influences a lot of young people. … It’s an art form that deeply shapes the minds of our youth.”

Animated shows such as “Kipo and the Age of Wonderbeasts,” “Craig of the Creek,” “Steven Universe” and “Avatar: The Last Airbender” are among those that have been praised for the diversity of their characters. Still, some note that none of these shows was created by people of color.

Rarer still are animated shows created for Black people, by Black people, like “The Proud Family.”

It’s a small but notable shift that actors and creators behind shows such as “Big Mouth,” “Central Park” and “The Simpsons” have declared it’s time for their nonwhite characters to be voiced by actors of color. It’s an issue that those like comedian Hari Kondabolu have been speaking up about for years.

But authentic representation in animation is multifaceted and involves more than just examining the race of the character and his or her performer. Writers and artists also bring specific cultural perspectives to their work.

“If there is a story that is about a Black person or speaks from the Black perspective, having an artist that has that perspective is important, because when artists are brought to a job, they have this chance to bring things to the story that may not have been [by] someone that’s non-BIPOC,” Singleton said.

Smith considers it every animator’s responsibility to understand the types of characters he or she is tasked with shaping onscreen in order to breathe life into them — because details like how the characters move are also a reflection of who they are.

“Visually onscreen [the character] is Black and was voiced by a Black person, but did it really feel like a Black person?” Smith asked.

He explained how “The Proud Family,” which originally aired on the Disney Channel from 2001 to 2005, was very specifically intended to reflect “this sort of potpourri of us Black folks, as opposed to one specific brand of Black folk.”

“What we deal with in every animated film or TV show is that one person has to hold up all things Black,” Smith said. “Totally unfair. It’s not a real thing. Having this show was allowing us to paint the backdrop of lots of Black people onto a lot of different characters.”

For the Black N’ Animated team, the path forward is clear: Hire more Black talent and provide them support and opportunities to advance in their careers.

But that will take more than studios just reaching out to the Black animation community right now.

“There’s a lot of talking going on, but what’s going to matter is the follow-through and the accountability,” Williams said. “It’s going to come down to the leadership of the different animation studios to actually follow through and support their Black employees.”

“It really takes assessment of the culture,” added Magruder. “It’s not helpful to hire a bunch of Black employees and then they enter a hostile, toxic environment that’s designed for them to fail. It really takes time and commitment to changing the interior culture to make sure it’s a safe place for people to work, specifically marginalized people.”

Because of the long production time in animation, even the most urgent of changes may not be immediately visible. (At least one is already in the works: Last week, HBO Max announced a forthcoming TV series from Matthew A. Cherry, based on his Oscar-winning short, “Hair Love.”)

Shaw believes that this makes it all the more important for studios to make a real effort to invest in Black talent as well as Black-owned studios and businesses.

The industry needs to start “seeing that you have to be an active participant in revolutionary change and not just a passive bystander as those on the front lines do the work,” Shaw said. “It’s time for the industry to devote itself to betting on people’s potential and investing in those people and giving them the opportunity to rise. Because we will. Black talent is there, we do exist, and we will rise.”

Original article was published here.

Facebook Comments