By ADAM HARRIS,

People protest to signal that they are fed up with the status quo. But protest is rarely singularly focused. People are in the streets this summer over the murder of George Floyd, but the current racial reckoning in America goes far beyond lethal policing. People are in the streets because Black students are five timesmore likely than white students to attend highly segregated schools. Because Black unemployment is regularly twice the white unemployment rate. Because racist housing policies have locked Black families into unequal neighborhoods and out of the prospect of building wealth.

Meanwhile, the policy responses to the protests have thus far been singularly focused on police brutality. State leaders have already signed a string of changes into law. Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds signed a bill restricting choke holds; New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed bills that would punish officers who kill someone after placing them in a choke hold with up to 15 years in prison, that would make police disciplinary records available to the public, and that would require officers to give medical or mental-health attention to people they have arrested.

In the 18 days after Floyd’s murder, 16 states introduced, amended, or passed various police-reform bills. But to be effective, efforts to combat systemic racism must stretch as far as the inequality itself does. That work is now beginning in city councils and statehouses across the country—largely in Democratic-leaning states—where lawmakers are being pushed to act on discriminatory policies.

Activists in Hartford, Connecticut, are petitioning local and state officials to eliminate racist zoning laws that block affordable-housing opportunities and segregate the city. In Wisconsin, board members for Milwaukee’s public-school district are writing a regional desegregation plan for the southeastern part of the state. Two weeks ago, when the board members voted on the resolution to begin their work, it passed unanimously.

“This movement started with dealing with criminal-justice reform and police reform—dealing with the institution of mass incarceration—but not stopping there,” Jamaal Bowman, who defeated Representative Eliot Engel to win the June primary in New York’s Sixteenth District, told me. Bowman is an advocate of the Green New Deal, universal health care, and a housing plan that emphasizes public housing and the enforcement of fair housing standards. “These are all interconnected policies that are rooted in equality and justice for all people and making sure we do all we can to uplift the working class and the poor,” he said.

Practical things can be done to address some of these disparities—not just big ideas that upend accepted norms, but also baby steps to keep momentum going. In education, activists are pushing leaders to reconsider how wealth is hoarded in predominantly white school districts. If states pooled property-tax dollars and distributed them evenly to schools rather than allowing accumulated wealth to dictate at least part of school financing, American education would look more equal, Rebecca Sibilia, the founder of EdBuild, a nonprofit focused on school funding, told me. But many Americans believe that local control of a school district means keeping all of their money there, she added.

Meanwhile, federal lawmakers are trying to knock down barriers to housing. This month, in a move led by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the House of Representatives voted to repeal the Faircloth Amendment, which has stymied new construction of public housing in the United States for decades. But the measure is doomed in the Republican-controlled Senate, which has limited its response to Floyd’s killing and the subsequent protests to proposing a police-reform bill that was due to fail from the beginning.

White Americans have stolen Black Americans’ land. They have stolen their property. In some places, there is a 20-year life-expectancy gap between white and Black people. Those gaps will take time and money to close. Bowman packages the reforms he believes the country needs as a new “Reconstruction agenda”—which includes free college, a wealth tax, and baby bonds. But his agenda begins by reconciling with history. That reconciliation would inevitably require some form of reparations, Bowman said. He didn’t articulate what those reparations would look like, but stressed the need for them.

Bowman, who after winning the primary will likely win the general election in a heavily Democratic district, may discover that many of his new Capitol Hill colleagues share the sentiment. Several House Democrats, including Representative Karen Bass of California, believe that H.R. 40—the bill that would create a commission to study the legacy of slavery and examine reparations proposals—could be voted on before the end of the year. That’s the least Congress could do, Representative Gregory Meeks, a co-sponsor of the bill, told me, “so that people can catch up and get access to things that everyone else takes for granted.”

For progressive activists, the national mood seems promising. But Americans have watched the story of civil unrest and policy stagnation unfold on a loop for more than a century. “No republic is safe that tolerates a privileged class, or denies to any of its citizens equal rights and equal means to maintain them,” Frederick Douglass wrote in The Atlantic in 1866. His words were aimed at the Reconstruction Congress tasked with rebuilding America after the Civil War.

Nearly 100 years later, in 1960, three decades before he would enter Congress, a young Gregory Meeks could spy his elementary school across the street from his public-housing complex in East Harlem. Meeks had just completed second grade when a school official, concerned about his growth, told his mother to get him out. The books at his school were old. There were few, if any, after-school activities. His educational development would be stifled there, the official said. So, alongside one other Black student, he went to another elementary school in a white neighborhood off York Avenue, dozens of blocks south, on the Upper East Side.

Four years later, on July 16, 1964, protests and riots erupted in New York after a white police lieutenant shot James Powell, a Black ninth grader. Two bullets pierced Powell’s body, killing him, not far from Meeks’s new school. The protests over the killing lasted for six days; the demonstrators called for an end to police brutality and for equal protection under the law. Witnesses said the 15-year-old threw his arm up to protect himself when the officer pulled his gun. The officer was acquitted by a grand jury after maintaining that Powell had lunged at him with a knife.

Meeks thinks a lot about the things that haven’t changed, how the issues of his childhood mirror the issues of today. “I’d always wondered why they couldn’t just fix the school that was right across the street to make sure that it would be good for all kids,” he told me. “It’s time for an accounting to be made in this country, if we really want to get to the root causes of the problem of racism in America.”

Original article was published here.

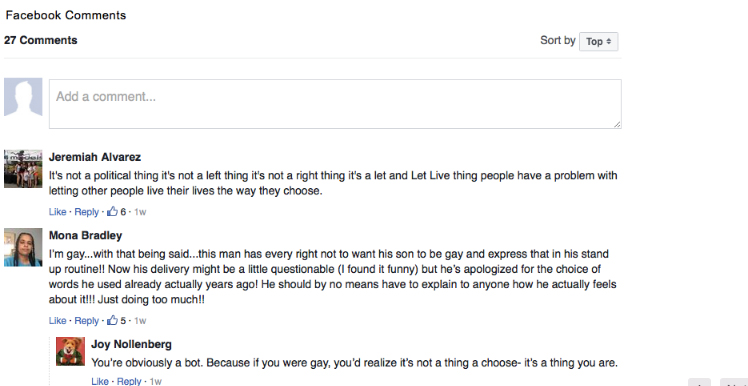

Facebook Comments