BY WESLEY LOWERY,

Congressman Al Green fidgeted in the front row of George “Perry” Floyd’s third and final memorial service, held here in the city where the slain man had spent much of his life, as he rehearsed in his head the speech he’d spent the night before preparing.Ads by scrollerads.com

Green had been in the living room of his Houston home when he first saw the excruciating cell-phone video on the news: a white Minneapolis police officer nonchalantly kneeling on the neck of the 46-year-old Floyd for nearly 9 minutes. The handcuffed man desperately crying that he can not breathe. The bystanders urging the officer to stop. His cold refusal to acknowledge their pleas.

Floyd’s body had been flown back to Texas to be buried. But first, there would be a funeral at Fountain of Praise church, one of the largest churches in Green’s district, at which the congressman had been asked to say a few words.

But now, as the service began, Green was struck by the words of the church’s pastor Remus E. Wright, who urged congregants to maintain social distancing, avoid getting too close, and keep masks over their mouths and noses. The coronavirus pandemic was lurking. And no life, the pastor stressed, was expendable.

Green couldn’t shake that concept—that we can’t afford to lose one more life. That now is the moment for drastic, desperate action. By the time he was summoned to the stage, the congressman had torn up his speech.

The death of George Floyd has prompted a generational national reckoning with race and justice unlike any seen in the United States since the LAPD beating of Rodney King, which was also captured on bystander video, in the early 1990s. Yet Floyd is just the latest to join a roster of black people killed by police in recent years: Laquan McDonald, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, Philando Castile, Alton Sterling, Korryn Gaines, Botham Jean, Breonna Taylor.

For years, black activists and organizers have demanded a complete upheaval of the criminal justice system, yet their demands have been met with skepticism from the public and promises, often unfulfilled, of piecemeal reform from the police. But this time, after Floyd’s death, could be different. Polling shows that a majority of white Americans now agree that there is something systematically unjust about American policing.

“I’ve actually been really emotional,” Amber Goodwin, a longtime activist in Houston, who has worked on issues of gun and police violence, told me, adding that the conversation about changing American policing has seemingly evolved overnight. “I’ve always believed that another world was possible.”

Rather than contemplating body cameras and bias training, the public is now debating what it could look like to shift some responsibilities away from police forces altogether. The nation is asking: Where do we go from here? And it seems, Americans are at least momentarily willing to consider a radical answer in response.

“To see a person with a knee on the neck, that’s more than is tolerable for any conscience,” Green would tell me a few days after the funeral service, noting that the Floyd video had shaken the nation in a way unlike any other video before it. He’s worked on these issues for years, and can recite the names of half a dozen black people killed by the police during the years he led Houston’s NAACP chapter. The hard-earned reforms over the years have been important. But in this moment, the public appetite for change seems to finally match the urgency of the crisis. “This Black Lives Matter movement is moving the social consciousness of this nation,” Green added.

And so he ditched his prepared speech, in which he had planned to call for “unity” and declare that Floyd’s life could not be lost in vain.

“We are here because we have no expendables in our community,” Green declared from the stage. “George Floyd was not expendable. This is why we’re here. His crime was that he was born black.”

Moments later, the 72-year-old congressman used his place in the pulpit to unveil a historic proposal—the creation of a federal department, run by a Congressionally-confirmed cabinet position, to tackle American racial reconciliation.

“We have a duty, responsibility and obligation not to allow this to be like the other times,” Green urged. “We have got to have reconciliation…We survived slavery but we didn’t reconcile, we survived segregation but we didn’t reconcile, we are suffering invidious discrimination because we didn’t reconcile… It’s time for us to reconcile.”

‘We’re in the middle of a crucible moment”

Green’s call for a historic reckoning with America’s racial legacy was still ringing in my ears days later, as I sat in front of my laptop screen and dialed into the video conference link I had been provided. Determined to seize the moment, the Congressional Black Caucus had convened a forum on police violence and accountability, and asked a slate of black activists from across the country to testify. They had also invited me.

For the last six years, I’ve spent most of my time writing and reporting on police violence and the movement of young black organizers determined to end it. It wasn’t a beat I aspired to, or a story I had intended to tell, but rather an assignment seemingly provided by divine happenstance. In August 2014, I was a Congressional reporter for the Washington Post who happened to have a bag packed when rioting broke out in response to the police shooting of Michael Brown Jr. in suburban St. Louis. Two days after my arrival in Ferguson, another reporter and I were arrested by local police as we attempted to file our stories from the dining room of a fast-food restaurant just up the street from the protests. Critics, some within my own profession, insisted that the arrest had made me “part of the story,” and that I should be removed from the assignment. That made me even more determined to dig in my heels. In the half of a decade since, I’ve made police-accountability journalism and the stories of those impacted by the failures of American policing into my life’s work.

In 2015, my colleagues at the Washington Post and I launched Fatal Force, a national database tracking fatal police shootings that grew directly out of our reporting on the ground. The black residents and protesters who I’d interviewed in Ferguson insisted that the police were routinely killing black men and women in the streets. Meanwhile, the police and their unions insisted that just was not the case—they rarely killed anyone, they claimed, and on the rare occasion that they did, the person had it coming. The problem was either a flaw in the system, or a series of isolated incidents. Two competing narratives, driving a national debate over race and policing.

Yet, stunningly, no reliable national data existed to settle the question. It was unclear how many people the police were killing, who those people were, and under what circumstances they were dying. So The Post began tracking every fatal police shooting we could—relying on details provided by local news coverage and then supplemented by additional reporting of our own. In the five years that followed, we recorded nearly 5,000 fatal police killings by police—about 3 per day—and discovered that black Americans are killed by the police at at least twice the rate of white Americans.

One of our followup investigations would document how even fired police officers are often able to get their jobs back. Another documented the extent to which black communities are overpoliced yet underserved—the most violent areas of major American cities are also places where murders are rarely solved.

The American public now broadly agrees that there is a problem with race and policing. But a new debate has emerged: how deep and wide is that problem? The activists in the streets have been clear—they believe American policing, which in much of the nation descends directly from slave patrols, is systemically racist and fundamentally broken.

Where do we go from here? As I testified to the CBC, the role of a journalist is not to provide the answers, but rather to document, in excruciating detail, the extent of the problem. And so, when asked where we should go from here, I deferred to the activists, organizers, and the black Americans who have taken to the streets.

“We have truly tried it all,” testified Jeremiah Ellison, a Minneapolis city councilman and former street activist who spoke before me, ticking off all of the reforms his city has attempted that have failed to fix policing. He’s said he’s given up on police reform, and is now one of the leading voices advocating the abolition of policing as it is currently constructed. “We give police an incredible amount of trust. And they deserve an equally incredible amount of accountability when they break that trust. Instead, accountability eludes them entirely.”

“In my experience and my community’s experience, the role of police has been a really violent force,” testified Patrisse Cullors, one of three co-founders of #BlackLivesMatter and chair of Reform LA Jails. “What I’ve witnessed in the last 30 years is a deep investment into policing and incarceration, and a deep divestment from all of the things that help and support communities that are in need.”

For starters, at least, the activists argue that the police need to no longer be tasked with dealing with things like mental health, school discipline, drug and alcohol issues and nonviolent conflict resolution. The buckets of money being poured into police departments—at times the single biggest expenditure in a city budget—should be directed into other community services and resources.

“We’re in the middle of a crucible moment in this country,” Phil Agnew, another young black activist, would tell me a few days later. Agnew likes to say he was radicalized while a student at Florida A&M University, following the death of Martin Lee Anderson, a 14-year-old black boy who collapsed while doing a required workout at a boot-camp style youth detention center in Florida. When he first entered college, Agnew thought the disparities facing black Americans must be their own fault. But the more he read, and the more he learned, he realized the entire system of American life had been stacked against them. Later, Agnew helped found the Dream Defenders, one of the most influential activist groups to emerge following the 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin. Most recently, he and Tef Poe, a Ferguson activist, launched Black Men Build, which hopes to organize and mobilize black men to be politically and socially engaged in advance of this November’s elections.

The next steps, Agnew said, need to be the creation of a world in which black Americans have the same likelihood of health care, clean water, job opportunities and quality education as their white neighbors. “Black people need to have the power to determine what our lives look like in this country,” he said.

Yet even as the activists insist that now is the time for sweeping changes and a deep reckoning with how the horrors of our nation’s history inform the inequities of our country’s present, the conversation in Washington remains much more narrow. Powerful Republicans and Democrats alike are offering legislation that, if signed into law, would undoubtedly increase police oversight and transparency, yet fall well short of the type of radical rethinking of American policing that the activists advocate. As the people in the streets call for abolition, the country’s leaders say they’re now ready to offer up reform.

“The nation is fed up with seeing the same situation play out over and over and over again,” said South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott, the sole black Republican senator, who has been charged with leading GOP police-reform efforts. The video of Floyd crying out for his mother as he died “broke the back of the American psyche,” Scott told me. “Enough is enough already.”

A crucial component of his legislation is a body-camera requirement, a proposal he began to advocate after the 2015 police shooting of Walter Scott, an unarmed black man, in Sen. Scott’s hometown of North Charleston, S.C.

In that case, the officer initially claimed to have been in a desperate struggle for his life when he pulled the trigger. But then a bystander released a cell-phone video that showed Scott running away as the officer opened fire, shooting Scott in the back as he fled. While body cameras don’t prevent such shootings, Scott conceded, they at least allow the public to see what truly happened in a given incident, and provide a better chance that officers will be held accountable.

“If a picture is worth 1,000 words, then a video is worth 1,000 pictures,” said Scott, who spoke to me on the fifth anniversary of another tragedy in his home state: the racist massacre that left 9 worshippers dead in Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, shot and killed by a white supremacist.

The extent to which the GOP has empowered Scott marks a significant shift for a caucus that just years ago framed any call for policing reform as an attack on all police officers. And yet the senator must walk a rhetorical tightrope. His colleagues still loathe the suggestion that the criminal justice system is “systematically” biased against black Americans. And so Scott himself has avoided—even criticized—the term, even as he provides personal anecdotes that offer proof of such systematic bias.

“Can I identify racial outcomes in the law enforcement community that makes me feel like more of a target? The answer to that is yes. Does that speak to systemic racism? I don’t know. I don’t come to that conclusion personally.”

For decades, he’s been routinely pulled over and ticketed for what he says can only be considered “driving while black.” Back when he was on his country council in South Carolina, Scott was pulled over by police seven times in a single year. Since first coming to Congress, he’s been stopped by the police at least four times while on the grounds of the United States Capitol. On one occasion, Scott was pulled over while driving to visit his grandfather in a poorer part of town, years into his time as an elected official, and soon found his car surrounded by at least four police officers.

“As a person who has been racially profiled, it pricks at your soul, it makes you feel small. It makes you feel powerless and frustrated,” Scott said. But isn’t that, definitionally, systemic racism, I asked Scott?

“You guys in the media can fight over the philosophical definition of something, but I don’t have the luxury of doing is having that fight…What you call it…is important… it just isn’t that important to me right now.”

Setting aside the rhetorical debate, Scott and his Democratic colleagues do agree on something else: whatever legislation they end up passing will still fall short of eradicating the issue. “I’m looking for something that stops hate from manifesting, I don’t see anything in their legislation or mine,” Scott said.

None of the proposals put forth by either piece of legislation would have necessarily kept George Floyd alive, and neither guarantees that another George Floyd won’t meet the same fate. The passage of either proposal, or a compromise that combines them both, would at once be the most sweeping piece of police reform passed by Congress in a generation, and also largely inconsequential as it relates to curbing the number of police killings.

“It’s all tinkering around the edges,” said Jonathan Smith, one of the Justice Department’s top civil rights officials during the Obama administration, who oversaw the investigation of the Ferguson Police Department after the death of Michael Brown. “People want to do something, so people are grabbing for low-hanging fruit,” Smith said. “But it’s not going to solve the problem in any meaningful way. It’ll let people feel like they did something.”

“I think what we’re witnessing is, quite frankly, the birth of a new nation. Childbirth is very difficult, but we’re going to make it,” CBC chairwoman Barbara Lee said when it was her turn to question the panelists during the hearing.

“Many of my white contemporaries especially are finally waking up to begin talking about racism, specifically systemic racism,” said Lee, who has introduced legislation that would create a truth, racial healing and transformation commission in the United States. “But they’re not clear about the historical context as it relates to slavery and how it’s manifested today in policies and programs and funding priorities and in the brutal murder of black men and women by the police.

A few days later, I called Congressman Green to ask how such a reconciliation process would work. As we spoke, he sat in his office, flanked by hand-drawn portraits he had commissioned of Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela. Across the room hangs another hero, Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman ever elected to Congress, who boasted in her campaign slogan that she was “unbought and unbossed.”

Chisholm, Green told me, was a “liberated Democrat,” willing to tell the truth even when it made others in her party upset with her. And it’s in that spirit that Green has joined Lee and others in calling for the United States to undergo a reconciliation process similar to those undertaken by post-Holocaust Germany and post-apartheid South Africa. Under Green’s proposal, the president of the United States would create a Department of Reconciliation, overseen by a Senate-confirmed cabinet secretary.

This person would be tasked with overseeing national and localized efforts to empirically document, educate the public, and then proposed remedies for the extent to which our nation’s original sin—centuries of slavery, followed by decades of legalized discrimination and oppression—still weigh down black Americans. The budget for such an office would fall under the Department of Defense, Green said, since future lawmakers would be loath to ever approve cuts to defense spending.

It’s striking, experts say, that the United States has never undergone such a process. While it’s true there have been commissions—the Kerner Commission after the riots of the 1960s, and the Christopher Commission after the riots of the 1990s—the federal government has never devoted significant resources to providing a sweeping corrective to the enduring damage wrought by American slavery.

“If you look at countries comparable to the U.S. in their long histories of racial inequality, all of them except the United States have gone through some sort of public reckoning of that past,” said Kathleen Belew, a historian who has studied reconciliation processes and author of Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America. “There are ways that racism and white supremacy are deeply hidden inside many aspects of our society. A truth commission gives us an opportunity to get it all out on the table.”

It’s a process that’s played out before, at the local level. Activists in Greensboro, N.C. launched a truth and reconciliation process following the 1979 massacre in which white supremacists shot and killed five anti-racist protesters. In Maine, Native officials underwent a truth and reconciliation process to explain and address why tribal youth were both overrepresented and mistreated in the state’s child welfare system. And in Detroit, local activists pressed the state for a truth and reconciliation commission to definitively document the public policy decisions that resulted in the region’s stark racial segregation.

“The best thing that can come from a truth commission is that we narrow the range of permissible lies that we tell ourselves as a community about our own history,” said Jill Williams, who ran the Greensboro commission and has advised on others across the country. I think that could be helpful to America.”

One of the key components of any such commission is to establish a mutually accepted historical narrative. While we all live in the same nation, white Americans and black Americans believe fundamentally different things about what happened in our shared pasts, much less about how it still affects us all today. And how far off are we from having that type of shared history? Are we close?

“Oh, come on. No!” exclaimed Smithsonian Institute secretary Lonnie Bunch when I posed him that question about three weeks after George Floyd’s death.

“You learn a lot about a country by what it remembers, but even more by what it forgets,” Bunch added, once he’d stopped laughing at me. “I was struck, years ago, by a letter I received where somebody said that America’s greatest strength is its ability to forget.”

Few in recent history have done as much work as Bunch to force America to remember. After years running the Chicago History Museum, Bunch served as the founding director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture—affectionately nicknamed “the Blacksonian“—before being named the first black man to ever oversee all 19 Smithsonian museums. To walk the halls of the Blacksonian, from its underground exhibits on slavery to its ground-floor exploration of civil rights to its towering tributes to black sports and culture, is to be confronted by the extent to which the nation we now occupy has been crafted by its past. Neither the inequalities that plague us today, nor the fight to upend them, can be separated from what has come before.

“There’s a lot of reason to recognize how today is tied to the arch of history, how the struggle is ongoing,” Bunch said, nodding to the protests surging in American streets, comparing the energy of this moment to the Civil Rights push that followed the Brown v. Board of Ed. decision and the murder of Emmett Till. “And the struggle takes resilience. It’s not always one big moment where there will be fundamental change. But what history tells you is that there are moments where you see the country take a giant leap forward.”

Once a shared historical narrative can be established, a reconciliation process can begin. “Restorative justice is a set of values,” explained Fania Davis, executive director of Restorative Justice for Oakland Youth. “It’s a theory of justice that brings together everyone affected by wrongdoing…We make mistakes. And we hurt people by those mistakes. But we can make amends for those mistakes, we can say sorry and we can take action.”

Davis is an elder in the movement, into which she was violently thrust after two of her childhood friends were among those killed in the 1963 Birmingham Church Bombings. “A big part of why you’re talking to me today is that I left that experience with this deep yearning to be an agent of social transformation,” Davis told me.

She began working with the Civil Rights Movement, and then the Black Power Movement, and then the anti-apartheid movment, and then the student movement. Her former husband, a Black Panther, was shot by a police officer who had entered their home as part of what was then-routine surveillance of black activists. When her sister, Angela, was arrested and held on murder charges (she’d later be acquited), Davis traveled the world raising public support for her release. It was that fight that inspired Davis to become a civil rights lawyer, and later to undertake the study of restorative justice.

While the American justice system asks what rule was broken, who broke the rule, and how severely should we punish them, a restorative justice framework asks who was harmed, what their needs are, what the responsibilities of the person who did the harm are, and how we repair that harm and meet those needs.

Like many activists, Davis had been heartened by the newfound national conversation around defunding police departments and replacing them with social services, and she praised the steps taken by the Minneapolis City Council to disband their police department—and hopes that whatever emerges there next is a community-led restorative justice process.

She also hopes other municipalities follow Minneapolis’ lead, and endorses the idea of a nationwide effort to undergo reconciliation. “This is the first step in creating an amazing process that will allow us to imagine a public safety system where black lives matter.”

“It’s way bigger than the police”

Pastor Patrick “PT” Ngwolo met me at halfcourt just after 5 p.m., the Houston heat hanging in the air as a handful of children dribbled basketballs twice the size of their heads. The courts that sit in the center of the Cuney Homes, the city’s largest public housing project, have four backboards but just two rims. “George Floyd,” someone had scrawled in orange spray paint beneath each of them.

Cuney is a 600-unit project known colloquially as “The Bricks”—for the bland tan-and-red slabs that make up the outer walls of its two-story apartments. It’s located in Houston’s Third Ward, the center of the city’s black politics and culture: it’s raised generations of black artists and writers and politicians and a musician you may have heard of named Beyoncé. Yet even the Third Ward provides a tale of two cities. There are blocks of massive old homes, once belonging to the Jewish residents who lived here before the black people moved in. And then there’s “The Bottoms,” the low-lying stretch of projects, auto-body shops and corner liquor stores tucked next to Texas Southern University, the historically black college founded to serve the black students excluded from the University of Texas.

George “Big Floyd” was well-known in The Bottoms, where he spent most of his life living in a white one-story home on the edges of Cuney projects. Few here can recall precisely when they first met Big Floyd. He had just always been there, a fixture like the rusting metal clothes lines that hang between the apartments. When Ngwolo showed up a few years ago to start a church, Floyd’s mother was on the housing complex’s residents’ council, and helped him get permission to hold church outreach events on the basketball court. Soon, Floyd himself had offered to help, telling the pastor to use his name if anyone ever gave him trouble.

“He provided a lot of guys mentorship and advice,” Ngwolo said of Floyd, likening him to a neighborhood mayor. Floyd was an elder statesman. In a part of town where many men don’t survive their teens, he had lived long enough to meet his grandchildren. “If you’re meeting someone of note in Third Ward, they know Big Floyd.”

Ngwolo and I walked a block or two to meet up with J.R. Torres, a 27-year-old, who had known Big Floyd for years. Torres’ sister has a child with Floyd’s longtime best friend, and so Torres got to know him well over the years. He’d initially scrolled past the video in his Instagram feed, but then his sister texted him. The police killed Big Floyd, she told him. It was only then that he realized the man he’d seen dying on social media was the guy from his neighborhood, the one who’d always offered an encouraging word and begged him to stay out of trouble.

“It was unbelievable,” Torres told me. Even in a part of town that’s used to burying its young, the cruelty with which Big Floyd’s life was extinguished has left people in a state of infuriated paralysis. “We were actually looking at the life being taken up out of this man.”

The three of us drove to the other side of the projects in Torres’ white Buick Lacrosse—the funeral program from Big Floyd’s memorial displayed on the dashboard—until we arrived at the memorial. It was a massive blue display, in which the slain man is depicted with a halo and angels wings. “In loving memory of Big Floyd,” the tribute reads “Texas Made. 3rd Ward Raised.”

There were about two dozen people gathered in front of the memorial, including Leonard “Junebug” McGowen, a popular Third Ward rapper who was perched atop the hood of his car, a mostly-smoked blunt burning in his hand, when Ngwolo and I approached.

“I think it’s way bigger than the police.” McGowen told me. He’d known Big Floyd most of his life, growing up as a childhood playmate of one of Floyd’s nephews. He still hasn’t watched the full video. “Look at our president right now. Look how he talks crazy…It’s way bigger than the police. The police is like their street team. The police is like their soldiers. They’re badged up so they can do whatever they want to us.”

The men and women here don’t always use the same words and frameworks as the activists who’ve taken to the streets across the country. But, when you listen, it’s clear they want the same things. They want to live in communities safe from violence, especially from violence perpetrated by those who are supposed to protect them. They see a system stacked against them from birth. They’re trapped in run-down housing, segregated into failing schools, without access to higher education or well-paying jobs. They live lives of difficulty and frustration, while being patrolled by police who don’t understand them.

“We don’t need white police in black areas. They don’t get it. It goes all of the way back to slavery. The minute a white person sees us you already know what’s the first thing on their head. You know how they judge us: Monster. Predator,” said Joshua Butler, 28, who was out at the memorial that night. He wanted to be clear that he doesn’t think all police officers or all white people are personally racist. Still, he said, too often, people who haven’t grown up here, who haven’t lived these lives—especially police—just don’t understand. “Y’all don’t know how it feels to open up the ice box and see nothing for a week straight. You could never stomach that.”

After about half an hour of conversations, we climbed back into Torres’ car to drive back to the basketball courts, and I asked him for his story. He’d grown up here, in The Bricks, and went to Jack Yates high school just up the street. His counselors and teachers helped him enroll in a nearby community college, but he didn’t last long—on his first day of classes, he got discouraged when he couldn’t locate the correct classroom. Days later, he got picked up by police and charged with marijuana possession. He spent a week in jail, and soon had abandoned his aspirations for higher education. In the years since he’s worked a series of odd jobs—lots of landscaping to supplement his gambling winnings. He wonders if he’ll ever leave The Bricks. He’s not betting on it.

“They have to want to fix it,” Torres told me of a system that he and black Americans across the country know is stacked against them, “If they don’t want to fix it, it ain’t gonna get fixed.”

And you don’t think they want to fix it? I asked.

“Not at all,” Torres replied.

Original article was published here.

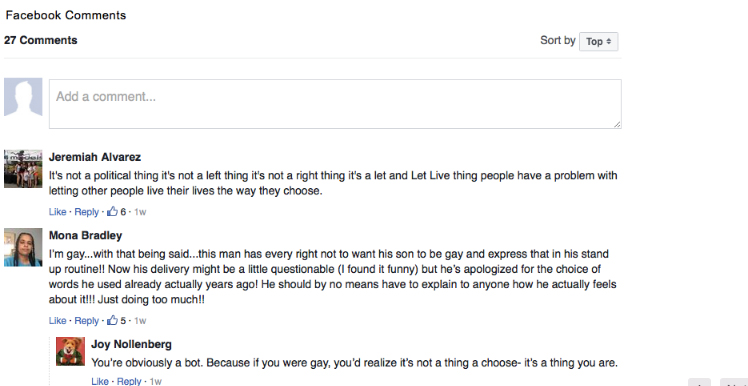

Facebook Comments