Glory Edim began building her empire of knowledge at an early age.

The founder of Well-Read Black Girl and author debuted her literary kingdom in the form of a digital book club that ensures black women who love reading, writing or both have a space to connect. With monthly reading selections and Twitter chats based on books by black women authors, the Nigerian-American has not only helped fill a huge void, but nourished a demographic often forgotten or erased by the literary world.

Since its 2015 launch, Edim has developed Well-Read Black Girl into anannual book festival in Brooklyn and an anthology, both of the same name.

Edim’s work empowers black women to feel seen and tostart a revolution with their words. Between and beyond the pages, she is an author, a nerd, an advocate and a force. And she has no intention of slowing down.

As a part of HuffPost’s “We Built This” series for Black History Month, Edim talked to us about her passion for literacy, her vision for Well-Read Black Girl and the urgency of protecting black women.

What started your love for reading?

My love of reading started with my mom. She was my biggest champion — and still is — and she read to me as a child. She took me to the library constantly and she really planted the seed of literacy in my mind. I always wanted to emulate her. When I saw her reading the newspaper or reading a book in bed, I was drawn to that experience. We read together constantly, and it’s still something we share. And as I grew older, I wanted to know more about not just reading and the practice of it, but how you could find yourself within a book and how you began to self define.

As a young black woman, it was important for me to read women like Toni Morrison and Maya Angelou, Gloria Naylor — all these women left imprints on my mind and what it was to be a black woman. And the first person who introduced that to me was my mother.

Then I started exploring on my own and asking questions on my own. But my mom was the beginning of all that.

What was the first book that you read?

The first book I have a real memory of reading is this book called Honey, I love by Eloise Greenfield. It’s a collection of poems. I read that book with my mother. I was drawn to the illustrations because, in the book, there’s all these beautiful illustrations of young black women and they’re like jumping rope; they’re on the playground; they’re reading with their parents. I didn’t have a true reflection of a character looking like me or sounding like me until I encountered Greenfield’s book.

I read a lot of different things, but, in terms of seeing myself, that book was the first time. I also read Judy Bloom. I read Little Women. Even reading Babysitter’s Club or Sweet Valley High, I read those things, but it wasn’t like I made an intimate connection with them or saw myself in the characters. I was more interested in the plot or just the teenage suspense of it or the childhood nostalgia of it. It wasn’t because it was a character who looked like me.

How do you think your love of reading evolved through your formative years when you were going through these books, when you’re seeing yourself or not seeing yourself, or whether it be through casual reading or through required reading? How did your understanding of yourself as a young black girl who loves literature evolve?

I found a lot of comfort in reading. It was something I did to occupy my time, to help me learn more about myself. It was similar to someone who really loves basketball. You go out and play basketball every day, and you don’t really think too much of it. It’s something you just have a passion for. That is how I was when I was a little girl. I read everything that I could find because I enjoyed the rhythm of it. I liked being in bed under the covers, having a flashlight and reading — just having a book close to me and asking questions. I thought of books very much as my friends. I was a talkative child, and I was very curious. My mother would say I was rambunctious and a little bit too inquisitive at times, but it’s what fed me. It felt right to me. I never felt forced to do it. I just did it.

It’s such a blessing — now that I look back — that I was passionate and loved reading because it shaped my whole career. The reason why I wanted to study journalism when I went to Howard University is because I was interested in telling stories and I was very curious about the everyday story. It didn’t have to be something that was extra-extraordinary for it to be told, it just had to happen.

“I always wanted to know more about the characters, and I wanted to know more about people. And that formed my identity as a black woman very clearly because I always felt very confident in my opinion, even when I didn’t necessarily know everything about a subject. I knew I could read about it, and it made me become naturally autodidactic.

I picked that up from reading the newspaper, reading these different books and just being curious. That was instilled very early on. I always wanted to know more about the characters, and I wanted to know more about people. And that formed my identity as a black woman very clearly because I always felt very confident in my opinion, even when I didn’t necessarily know everything about a subject. I knew I could read about it, and it made me become naturally autodidactic. I had an understanding that this is how you get better at something. This is how you gain expertise. You educate yourself, and you read things to grow your knowledge.

At home, we had the old school encyclopedia and Britannica things. If I didn’t know a word, my mom would say go look it up in the dictionary. If I didn’t understand something that I saw on TV, go look it up. And as I grew older, and I ended up going to Howard, I always felt confident that I can figure this out. It made me be a more independent and resourceful person because I knew I could educate myself on a subject. I could read into expertise. I still feel that way. There’s still a lot that I’m learning about but I know I can get there through reading and through asking questions. And so that’s always been a part of my personality and really core to who I am as person.

I love that so much. I consider myself a nerd with my love of knowledge and of learning more, poking, prodding and figuring things out. I’ve always been like that. Do you consider yourself a nerd?

I 100 percent consider myself a nerd because if we are to define what nerd is, that’s just someone who is an inquisitive, curious, super-passionate person. And whether you’re nerding out on books or on film or on art, video games, technology — whatever it is, that means you’re immersed in it. And I definitely think I’m immersed in literature. I’m excited about it and I love finding my people. I love finding other folks who are excited about the same things, whether it’s books or art. Coming together in a community, being excited and nerding out on something, I think that’s dope.

That shouldn’t be a thing to be ashamed or afraid of. It should be celebrated. We all are learning and growing together. There needs to be more space to celebrate the things that we’re excited about.

“There’s more depth to the black experience and it really starts with our oratories and our narrators.

And there needs to be more space for us as black women to see ourselves reflected as nerds.

Exactly! When you have writers like N.K. Jemisin who can create whole beautiful worlds of science fiction and have the imagination to dream beyond what is in existence, that’s amazing. You need to have a nerd do that. You need to have someone who’s able to imagine what the world could be like. And I’m really excited that we are starting to embrace the word “nerd” more, and we’re actually seeing reflections of black women across genres — especially in science fiction.

And thinking about Afro-futurism, in a more powerful way that isn’t just service, really speaks to the fact that our identities are diverse and we’re not monolithic. We have beautiful narratives that span generationally across the diaspora. There’s more depth to the black experience and it really starts with our oratories and our narrators. Who are the people telling the stories? Who are the people creating the technology? Who are the people changing the algorithms?

It is so important that black women are always in the room and working across genres to make that happen and to imagine new worlds. I really think about imagining greater things for the future. And without that imagination, it’s going to be stagnant. We’re not all the same.

There’s a vastness to blackness that needs to be recognized, especially in media, especially in literature, in film. We were just talking about ”If Beale Street Could Talk,” that the beauty of that film and the texture and the richness of the color, all the things that Barry Jenkins does with his photography is so powerful because we’ve never been portrayed in film that way with such a beauty and such warmth. We need more filmmakers like that. We need more writers. We need more artists who are willing to share their imaginations with us and see blackness in a more beautiful and profound way.

You’ve created a community that embraces the love of literacy, the love of literature, the love of seeing themselves reflected in words because words matter. They mean things. When you set out to create Well-Read Black Girl, what were your intentions? What did you think it would become?

My first intention was to create a support system for myself. I was new to New York, and I didn’t really have a community here and my first instinct was to go to books to foster new friendships.

I have wonderful women in the book club who I now call dear friends, but it’s expanded beyond that, and it’s gone beyond this just space in Brooklyn where we meet. It really is an online community where people are advocating for one another. It has become a discovery tool where people can find new authors because my focus is still debut authors. I’m really trying to find emerging voices, folks who have just published their first book and they’re in need of support. They need people to buy their book.

The next step to that, which I’m really trying to grow into in 2019, is developing a system where we can advocate for one another and support each other through activism — whether you’re looking to run for office or you’re trying to bring attention to social issues in your community. You know you can rely on Well-Read Black Girl to amplify that and continue to spread the word. It’s gone from this one thing where I’m thinking about friendships and solidarity, but I’m also thinking about how can we expand these friendships and really support one another in other circles, politically.

Most recently I shared something that said very simply “protect black girls” after the Lifetime documentary detailing R. Kelly’s long-term abuse of black women. I thought it was the perfect opportunity to put the system into practice. Yes, it’s not necessarily connected to literacy, but it’s a platform where the stories are centered on the narratives of black women. And that is an important narrative. Sexual abuse does happen in our community and attention needs to be brought to it, and it needs to be stopped. It needs to be clear that there are consequences when you harm black women. And we can’t be ignored. We can’t be ignored politically, we can’t be ignored when abuse is happening rapid in our community.

I want to use Well-Read Black Girl as a tool to really continue to amplify our voices. Yes, in publishing, but beyond that. I’m super excited about all the incredible young women, women of color, black women who are running for office. They have my support. I’m just thinking so much more about social issues and the books that we can read to educate ourselves on certain issues.

I love that and it’s so necessary — especially when we talk about these issues that, quite frankly, get ignored because they’re at our expense.

I am super motivated by that because now that the platform is growing, and I do have the attention of different people. I want to use it for good.

I do my best to replicate the experience I had at Howard University. My college years were so informative for me and it was the first time that I really felt safe. I felt safe in my blackness and I felt — I don’t even know how to explain it. I really felt secure in that space. I have such a strong appreciation for it because once I left I was like “Oh, the world doesn’t even operate this way.” The world does not value blackness. It does not see us as regal. They don’t really value our opinions, especially as black women.

And the moment I stepped off that campus and I was struck with that reality, I was just constantly trying to bring that feeling back. I want to always let people know that their opinions matter and the things that they’re working on will be supported by other black women. If nowhere else, know that black women will support you. And that’s not without analysis or critique. I think it is important for us to critique one another and do so lovingly. But at the end of the day, I do recognize and have empathy for the things that someone is experiencing because I know that as black women, we can only relate to each other in that way.

That’s important for me. So I’m always trying to find that center where I can work and advocate for the rights of black women.

One thing that’s super evident in the short time that we spent together this afternoon is how much you stand on your ancestors’ shoulders. This is truly your passion, and this isn’t something that you’re just doing l for likes or for any kind of clap, but you truly believe in the work. So given that, given my kind of general assessment, who are the ancestors, the change agents, the black history makers that continue to inspire you to do this work?

Oh my goodness, well, I will start with my lineage. I am very inspired by mother and father. My mom is again, an avid reader and a historian. And my dad, who recently passed, also went to Howard. It’s part of our legacy. So, my parents definitely are the two anchors for my love of reading.

Beyond that, I would say I am really inspired by literary scholars, in particular, Mary Helen Washington. I read her book Midnight Birds continuously. Toni Cade Bambara, she was a professor but also a documentarian and a writer. One of my favorite books is her anthology, The Black Woman, as well as her short story collection Gorilla My Love. I love those two books so much. She talks about everyday people. She talks about the essence of what it is to be a black woman and the levels of it — looking at class, looking at intergenerational conversations. I just loved, love her work. She also at one point in her career was making a documentary. She just did everything.

I also really love Mary Evans. Her anthology was one of the first things I encountered at Howard. Gloria Naylor. I say her name and try to invoke her spirit in every conversation because I feel like her work has really been lost — with exception of like The Women of Brewster’s Place, which was turned into a movie. But there’s like Linden Hills and Momma’s Day. She is so iconic. I’m very inspired by Dr. Imani Perry who is an academic. Most recently she wrote a book called Looking for Lorraine, which is a tribute to Lorraine Hansberry.

There’s just so much knowledge to be taken from their experiences. And it’s crazy because I feel like I’m rereading a lot of stuff now. I’m going back, and I’m looking at the essence of what they were trying to communicate. What did they want the reader to take away from this? What was the context of the world that they were living in? What was happening politically? Why was it so essential for them to write this message at this point in history?

I think especially because of the political climate now, the things that artists are creating and what they’re writing and responding to is so heavily influenced by external. So I’ve just been going back and studying how do they do it. How do they stay inspired? How do they stay so resilient when things feel dark?

I especially love the later part that you said because history does repeat itself. And history does hold all the answers to how we handle and go about some of the issues that we face today.

They’ve essentially left us a blueprint. So how can we take the lessons from the work and implement them in our own lives and remain vigilant.

Definitely. Tools may be different, but circumstances definitely aren’t.

Yes, because racism is still rapid. The things that Toni Morrison was writing about, the things that Alex Walker was writing about, those ideologies and concepts are still very apparent in our culture now. We can learn a lot from the things that they shared with us.

It was Zora Neale Hurston’s birthday recently and I was reading Their Eyes Were Watching God. Everyone is so fixated on the love story in that book, but I had forgotten that it was a best friend story too. Zora Neale Hurston, or Janie I should say, is telling the story to her best friend. And I forgot the premise of this is really about friendship. She’s telling the story to her confident who she loves and trusts. There’s a sisterhood in that.

What are your hopes for the future?

My hope is to turn Well-Read Black Girl into a long-lasting institution and a space where we can celebrate black achievement. I would love for it to become an endowment of some sort where I could help fund debut writers. I would love to have an imprint. That’s something I’ve been thinking about really a lot in the last two or three years. If I was able to have an imprint of my own, but at the end of the day I really want it to continue to be a communal space where we can meet and foster connections. I want the festival to continue to grow — even if I’m no longer here on this Earth, I want it to live beyond me. 2018 was our second year. I’m planning for 10 years down the line, 20 years down the line. I’m trying my best to sow those seeds and build a foundation for that. That’s the vision.

My hope, also, is as we continue to grow people will come back, and they’ll have their books. They’ll say they had their start at the Well-Read Black Girl Festival or as part of the community and five years later, 10 years later, they’ll have their book.

Original article was published here.

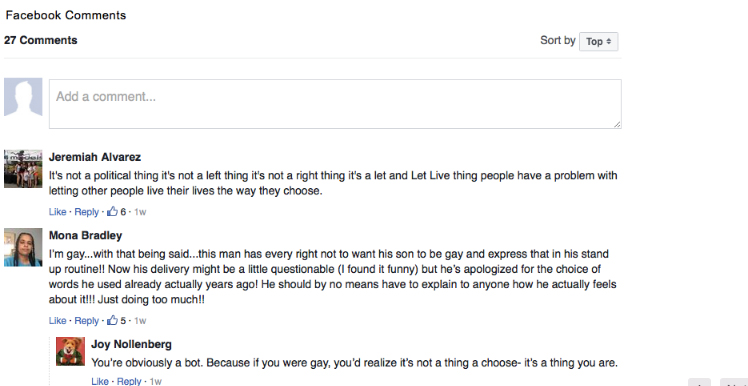

Facebook Comments