Tyler Perry is a household name in the United States, where his movies have made nearly a billion dollars. But in Britain, he is known mainly for playing the lawyer to Ben Affleck’s accused husband in “Gone Girl” — if he is known at all.

Some of the movies Mr. Perry has written and directed have received small international openings, most often in South Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Only one or two ever got anything close to a European theatrical push.

“I fought for it, I asked for it,” Mr. Perry said. But often he gets the same response: “Stories with black people don’t travel, don’t translate.”

For years, minority filmmakers have pushed Hollywood studios and distributors to get over a reluctance to promote their films worldwide. They are hoping that 2018 was the tipping point they have been waiting for.

This year “Black Panther,” “Crazy Rich Asians” and “BlacKkKlansman” all raked in money overseas, an unusual winning streak that challenged beliefs about the global appeal of actors of color.

Charles D. King, the chief executive of Macro, a financial backer of “Fences,” starring Denzel Washington, and the summer indie hit “Sorry to Bother You,” said he had seen examples of an industry shift. He pointed to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s and Warner Bros.’ full-bore promotion of the November boxing sequel “Creed II,” with its star, Michael B. Jordan, traveling with the film internationally.

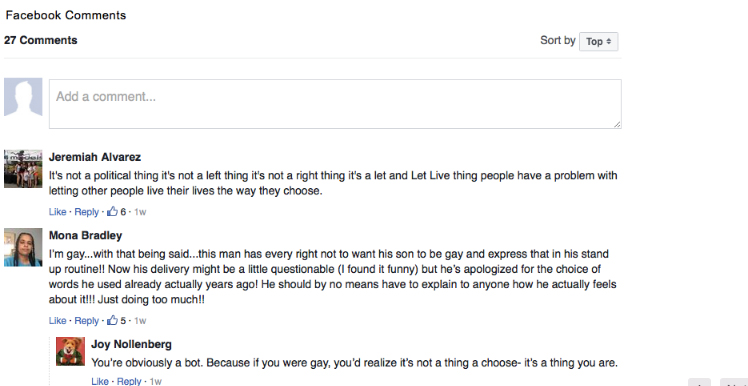

Of the longstanding belief that films need white leads to travel, Mr. King said: “We’re seeing pockets of progression, where the studio pushes the agenda.” $64 million at the overseas box office: “Crazy Rich Asians” benefited from strong champions inside Warner Bros.CreditWarner Bros.

Image$64 million at the overseas box office: “Crazy Rich Asians” benefited from strong champions inside Warner Bros.CreditWarner Bros.

International distribution is hardly a glamorous aspect of moviemaking. But with the global box office more important than ever to a studio’s bottom line, the prognosis for how a film might fare abroad has far-reaching implications for the size of its budget or whether it even gets made.

Representatives for major studios declined to comment for the record about the issue, though several privately insisted that their films were treated equally regardless of the stars’ race.

But publicly available data suggests that beyond some exceptions — the “Fast and Furious” franchise, and films starring Mr. Washington or Will Smith — movies with minority stars generally have not received the same international push as white-led ones.

Comparisons are imperfect, but in 2014, for example, the Kevin Hart-led remake of the romantic comedy “About Last Night” made $2 million more at the domestic box office than the rom-com “Blended”with Drew Barrymore and Adam Sandler, despite opening in 1,300 fewer theaters, according to Box Office Mojo, which tracks ticket sales. But “About Last Night” was released in only a fifth as many countries as “Blended.”

“Blended” did well internationally, either proving studios’ instincts right, or as critics suggest, showing what happens when studios put more effort behind white-led films.

Boots Riley, the director of “Sorry to Bother You,” starring Lakeith Stanfield, brought attention to the process when he complained on Twitter that “distributors r claiming ‘Black movies’ dont do well internationally and r treating it as such.”

While “Sorry to Bother You” went on to secure international distribution from Focus Features, industry insiders said that there was truth to the director’s charge.

Some film industry veterans familiar with studios’ thinking say the issue is about perceived risk.

If a film is deemed relatable only to a smaller domestic audience, like African-American moviegoers, executives have been loath to risk profits on what they see as an expensive gamble abroad. In that line of thinking, Mr. Perry’s trouble gaining traction overseas (his latest movie “Nobody’s Fool” has made just $227,000 in Britain) should be no more surprising than the failure of German or Italian comedies to find big audiences in the United States, where even some British hits, like “Johnny English Strikes Again,” barely registered. $40 million overseas: Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman,” starring Laura Harrier and John David Washington.CreditDavid Lee/Focus Features

$40 million overseas: Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman,” starring Laura Harrier and John David Washington.CreditDavid Lee/Focus Features

“The unknown mystery studio execs are always demonized, but they are investing millions and millions of dollars and face incredibly high risk and they have one weekend to get it right, and often they can’t,” said Hamish Moseley, head of distribution for Altitude Film Entertainment, a British distribution and production company. “And they are beholden to information they have, which is what other films have done.”

Executives also have pointed to the influence of China, the world’s fastest-growing film market, saying its audiences have aversions to black actors. The Chinese market, which has a quota system on foreign films, is more complicated than that; while “Black Panther” earned a relatively middling $105 million there, for example, “Star Wars: The Last Jedi” made less than half that amount. But China still weighs heavily in decisions on film budgets.

This year seemed to prove old industry assumptions wrong. By throwing muscle behind nonwhite filmmakers who drew deeply from culturally specific experiences, studios hit pay dirt.

“Black Panther” drew nearly half of its $1.3 billion revenues from overseas, and “Crazy Rich Asians” made a quarter of its $237 million earnings abroad. Foreign ticket sales account for nearly half of the $88 million “BlacKkKlansman” has made worldwide so far. Their success followed strong showings in 2017 by two films with nonwhite leads, “Get Out” and “Hidden Figures.”

Some stars have refused to wait for studios to lead the way. Borrowing a page from Will Smith, who took it upon himself to promote his movies overseas, Mr. Hart raised his profile by touring his comedy show around the world. Now nearly a third of his box office earnings come from overseas, a figure he is working to grow.

“The studios wouldn’t take the first step and promote him,” said Jeff Clanagan, who works closely with Mr. Hart as president of Codeblack Films, a division of Lionsgate. “So Kevin went and built this audience for himself.”

But Mr. Clanagan said that he still is being told there is a less of an international market for movies with black actors. He is developing a film about the civil rights icon Angela Davis, whose incarceration in the early ’70s inspired the global “Free Angela” campaign. Despite Ms. Davis’s historic cachet, Mr. Clanagan said that convincing Lionsgate’s international division of the film’s global viability is a challenge.

“They’ll say, ‘We can’t forecast international,’ but there is no data to support that assumption,” he said. (Lionsgate had no comment.)

Malcolm D. Lee, who directed the recent Kevin Hart hit “Night School,” which drew a quarter of its $102 million take from global audiences, believes the lack of success of some nonwhite films overseas might be due less to audience taste than to a lack of studio effort. “If they’re saying that ‘Well, it’s not going to work,’ it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy,” he said.

His 2017 film “Girls Trip,” became part of an accidental sociological test that seemed to prove studio critics right. That movie had a nearly all-black cast that included Jada Pinkett Smith, and was released within a few weeks of “Rough Night,” which starred Scarlett Johansson and a nearly all-white cast. Both were R-rated comedies about women on wild weekend getaways.

“Rough Night” opened in 3,000 theaters domestically and some 40 countries. It made $47 million worldwide. Then came “Girls Trip,” which opened in 571 fewer theaters and in half as many countries, but trounced “Rough Night” with box office receipts of $140 million.

Some industry veterans say that while studios’ international distribution branches know how to market big franchise films, they are not always as well suited for the kind of marketing that films with nonwhite casts might require.

Priscilla Igwe, managing director of the New Black Film Collective in London, said that American studio films starring people of color are often released in Britain with little fanfare and negligible outreach to black filmgoers or black press. Jan Naszewski, owner of New Europe Film Sales, a distributor in Warsaw, said of the studios: “The only thing they do is carpet bombing, paint-by-numbers marketing. They don’t know how to reach an independent audience.”

Terra Potts, head of multicultural marketing at Warner Bros., said the success of the meticulous campaigns she crafted for “Crazy Rich Asians” and the 2015 film “Creed” were the result of having unwavering champions for each film in the studio from the get-go, which is often an anomaly for films with black or Asian leads.

Asian tastemakers were shown cuts of “Crazy Rich Asians” throughout production, which helped lock in major community support, and among the first to see “Creed” were attendees at one of Sean “Diddy” Combs’s music conferences in Miami Beach. The films’ domestic success helped foment international interest.

“You really need people internally who believe in it, who are not going to take no for an answer, ” Ms. Potts said. “This kind of success doesn’t just happen.”

Facebook Comments